WWI: A world turned upside down, the war effort

By Sandy Vasko

A little over one hundred years ago, the whole world was in turmoil. Young men were being drafted, a thing that hadn’t happened since the Civil War.

Food was scarce, and some things could not be found at all. Rumors of German spies in our midst had folks looking twice at their neighbors, especially those with an accent. Patriotism was not encouraged, it was demanded. The simple life that people had known was gone forever, the world had turned upside down.

In April of 1917, President Wilson asked for a declaration of war, passed overwhelmingly by Congress. In that declaration, he also outlined what was to happen to those who were declared an enemy. Under the heading of “enemy” were the peaceful German settlers who had come to Will County to escape the oppression in Europe. The following rules were outlined for them:

- “All males over 14 years old of German descent, who have not been naturalized shall be liable to be apprehended, restrained, secured and removed as alien enemies.”

- Those who fit the above criteria shall not have in their possession at any time and any place any firearms, weapons or implements of war or components thereof, or any ammunition or silencer, arms of explosives or material used in the manufacture of explosives.

- An alien shall not have in his possession at any time or place, or use or operate any aircraft or wireless apparatus, or any form of signaling devices, or any form of cipher code or any paper, document or book, written or printed in cipher.

- Anyone found in violation shall have all property subject to seizure by the United States.

The list went on, but the above restrictions were enough. Many who had come to Will County when a child, had not been naturalized; many older folks could not pass the test in English. This meant that a good portion of the eastern part of the county were “officially” enemies. They lived in fear, hoping that something that was said to a neighbor would not result in their arrest.

The restriction about firearms were another problem. Almost every farmer had a gun, for use in hunting, killing livestock, shooting coyotes, etc. If a young German was caught hunting, it would mean jail.

The third restriction resulted in Germans being fired from their jobs as telegraph operators, as Morse Code was considered a cipher. Railroad linemen were also dismissed, as they used signaling devices.

Soon, those who did not fly a flag, or who did not join the Red Cross, or who spoke with an accent of any kind, or questioned the government, or looked young and healthy but did not join the National Army, came under suspicion from their neighbors.

The world had turned upside down, and even your old friends and neighbors had become potential enemies. The population looked for enemies everywhere, but the deadliest enemy was one they could not see.

In March of 1917, we read in the Wilmington Advocate: “Joliet and other cities are planning a fight against infantile paralysis (polio) which is expected to break out in this section. Our board of health should be in readiness to fight this disease at its first appearance, and if there is a way of keeping it from getting a start here let that way be adopted regardless of the cost.”

Polio is infectious and can cause death, paralysis and general muscle weakness. However, 70 percent of infected people show no symptoms at all, although they are carriers of the disease. This makes it even harder to quarantine the disease.

Two weeks later, diphtheria arrived in Wilmington: “Monday last, Ray Gadberry, son of Mr. and Mrs. A. J. Gadberry, was taken ill while attending school. That evening a physician was called who pronounced that the little fellow was suffering from diphtheria, and promptly had the home quarantined.”

Along with that article was: “Plainfield has more than twenty-five cases of scarlet fever, and despite the united efforts of the local board of health this disease seems to be on the increase.”

Farmers and their families who lived in isolated areas were less prone to get these contagious diseases. They had other problems though. With all the young men going to war, a labor shortage developed.

We read on August 17, 1917: “Farmers in this vicinity are complaining of a scarcity of farm hands to assist them in harvesting their crops and during threshing. Several farmers have been in town the past few days looking for men and offering as high as $6 per day (About $145 today).”

In addition, because of the war effort, every farmer had added more hogs to his farm, even those who were not hog farmers before, became one when the price of pork rose sky high. And where did all these new hogs come from? Why from other farms of course. Again, the unseen enemy, a virus, raised its ugly head.

We read on September 17, 1917, in the Wilmington Advocate: “Hog cholera has broken out in Joliet Township and Will county is facing another epidemic of this plague. The epidemic is said to be of a chronic type and for this reason has been raging among several herds in that township before its true nature was discovered.

“All of the animals in the herds have been vaccinated as an attempt to save them. All farmers in that vicinity have been warned by Manager Lisher, of the Will County Farm Bureau, that delays are dangerous, and that all hog owners will do well to see that their herds are vaccinated at once as a precautionary step.”

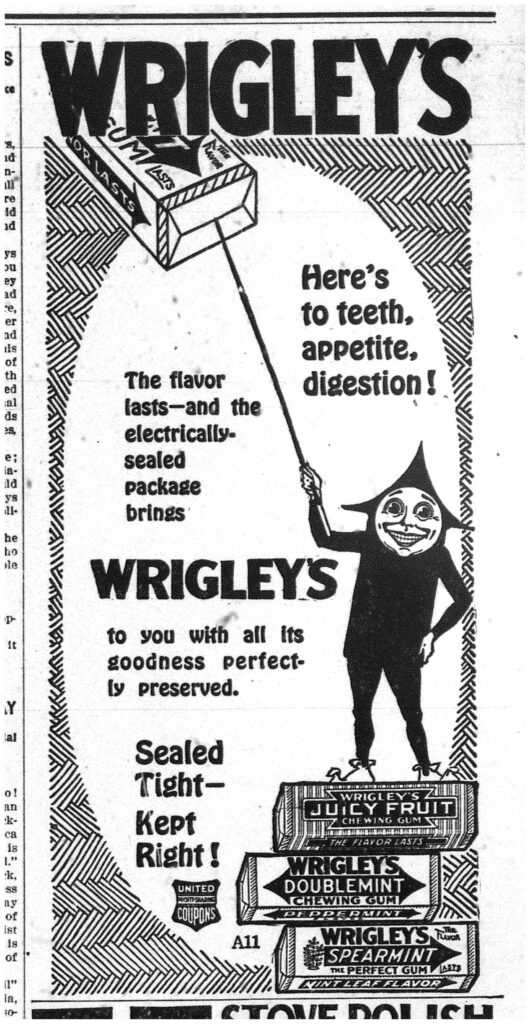

Indeed, it was difficult to keep morale up at home. The federal government encouraged all businesses to help with the morale problem by always showing a smiling face and indicating all is well with the world. One company that took this to heart was Wrigley’s.

In March of that year, their ad mentioned that it was used by soldiers at the front, along with Japanese girls in Tokyo, sheep herders in Australia and ox drivers in Singapore.

In September of 1917, it had changed. It now featured a sailor peeking out of a port hole with a big smile on his face. The ad said, “many a long watch or hard job is made more cheerful” by using their gum.