Civil War: May 1865, the long road home

By Sandy Vasko

Although the streets were full of people, it was strangely quiet. May blossoms filled the air, but black was everywhere you looked, over doors and windows, but mostly over the image of one thin, bearded man. That was what a nation in mourning looked like.

Abraham Lincoln was coming home. They had announced the route of the funeral train, and it was to pass directly through Will County on the C. & A. tracks. In Springfield, arguments were being had about the funeral arrangements. Special trains were being chartered for those who wanted to attend.

Others made plans to see the train at various stops along the way, or to simply see it as it passed through the depot or along the tracks. The May10 edition of the Wilmington Independent describes the funeral car’s passage through Will County:

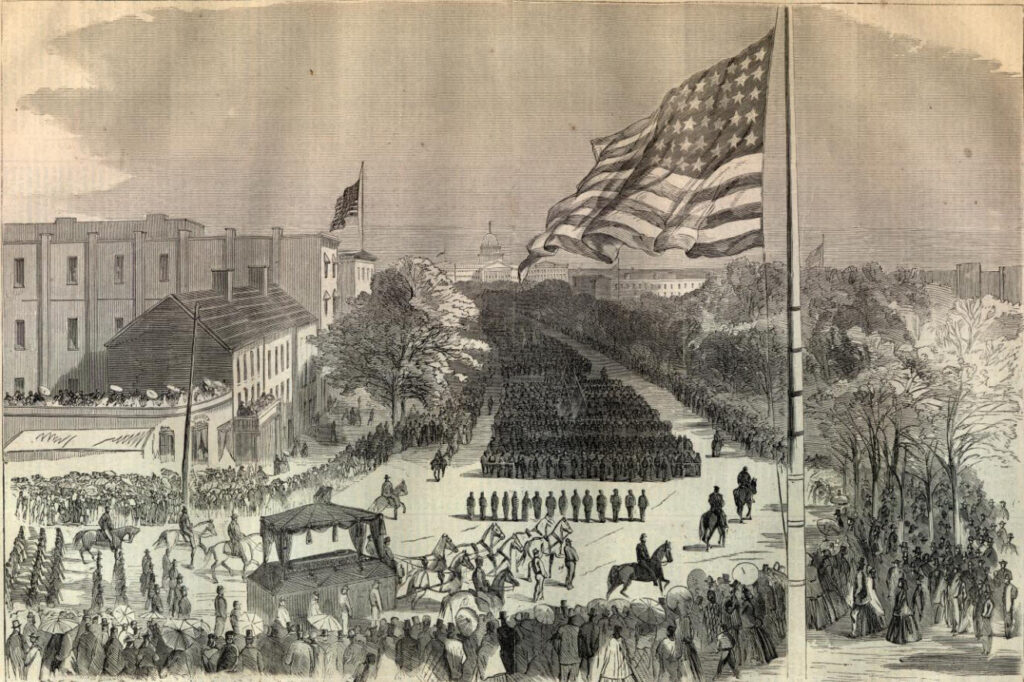

“The funeral train bearing the remains of President Lincoln left Chicago on Tuesday night and was met at every station between that city and Springfield by crowds of citizens, who stood with bared heads to pay fitting tribute to the memory of the illustrious departed.

“The depots were beautifully draped at every station. At Joliet the depot was handsomely decorated by the national colors and wreaths and evergreens. A very singular circumstance is noted. Just as the train was approaching a brilliant meteor shot across the heavens, and appeared to fall immediately over the funeral car, adding solemnity and beauty to the scene.

“The train arrived at Wilmington at about 1 o’clock a.m. Several of our citizens had decorated the depot in the most appropriate and beautiful manner, by emblems in the form of an asterisk, with the motto in the center, ‘Martyr yet Monarch,’ from which radiated the mourning colors, fastened by rosettes, beneath which draped the American flag. Above this was a portrait of President Lincoln, trimmed with evergreen. Surmounting all, at the center of the building, was perched an eagle. On the platform in front were eight or ten large vases, in which fires were burning, illuminating the whole with fine effect.

“Some forty torch bearers were drawn up on either side of the track, and bonfires were burning nearby. About 1,500 people had collected from our city and the surrounding country to witness the passing train, but were quite disappointed at the speed with which it went through.

“Orders had been given to come to a dead halt before entering the stations, and pass stations at a speed of 4 miles per hour. The engineer whistled for breaks down at the head of the grade, but for some reason they did not hold, and the train passed at about 20 miles per hour, with breaks set.”

Amid the national grieving, there were those who had a more personal reason to mourn. News was coming out of Confederate prison camps of even more deaths:

“Death of a soldier – Barton S. Walters, who enlisted in the 39th Illinois regiment in September, 1861, and re-enlisted in January, 1864, died at Annapolis, MD., on the 1st of March, from the effects of ill use in Southern prisons. At the battle of Drury’s Bluff, in May lst, in trying to save the Major of his regiment who had fallen badly wounded, he was taken prisoner by the enemy. He lived but a few days after reaching our lines. His body was brought to Minooka for interment.” Lists of men who had been held were published, and there was joy at finding a loved one still alive.

Men of the 39th were welcomed home during the third week in May. George Woodruff gives an overview of that brave regiment in his book, “Will County in the Civil War,”: “Our County lost in the 39th, 4 commissioned officers, two of whom were killed on the field. Several others were cruelly maimed. Twenty enlisted men from Will County died of disease, thirty more were killed on the field or died of wounds. Four died from imprisonment. Many others were wounded and suffered imprisonment. Surely the Yates Phalanx contributed its full share of precious life and loyal blood to the preservation of the Union.”

At home, there was a dark cloud hanging in the air, and its name was vengeance. W. R. Steele wrote almost gleefully of the treatment of Confederate leaders: “Jeff Davis has been manacled on both ankles, with a chain connecting them about three feet long. He stoutly resisted the process of manacling, and threatened vengeance on those who did it. Rather than submit, he wanted the guards to shoot him. It became necessary to throw him on his back and hold him until the irons were clinched by a son of Vulcan. (black man). No knives or forks are allowed in his cell, nothing more destructive than a camp spoon.”

June of 1865 was a strange time for the men still in uniform. The war was over; the rebellion had been put down. President Lincoln had taken his final ride. Now more than ever, time weighed heavily. Thoughts came rushing back, thoughts of comrades no longer with them, thoughts of battle scenes where friends were torn apart in an instant, thoughts of cold nights sleeping on the ground with little food, but mostly thoughts of home.

In George Woodruff’s book, “Will County in the Civil War,” an unknown correspondent from the 100th describes what it was like: “The time passed slowly. Everyone was anxious to know what was to be done with our regiment, whether we should now be sent home, or held to serve out the balance of our three years. The boys passed the time in playing ball, foot races, and other games.

“The review of the 4th corps, notwithstanding its reduced numbers, was a splendid sight. 12,000 brave men were marshaled in their best trim, now for display, and not for deadly strife, and for the last time! It added interest to the occasion that the review was held on our last battle field, the field of his glory, and ours, where the finishing stroke had been given to the rebel cause in the west. The city was out in holiday attire to witness the scene.

“On the 13th day of June, we broke camp, and folded tents for the last time, and started for home. Arrived at Chicago, Thursday, June 15th. Had a formal reception by the citizens of Chicago, and were addressed by Gen. Sherman on the 16th.”

Preparations were being made for the biggest best Fourth of July celebration ever. The editor of the Wilmington Independent wrote, “Now we always prefer, when feasible, to celebrate the Fourth at home. But on this extraordinary occasion, we favor the idea of the whole of Will County, meeting at our county seat, taking the hand of fellowship, laying aside our political opinions, and joining in one grand, glorious jubilee, such as the county has never witnessed before.”

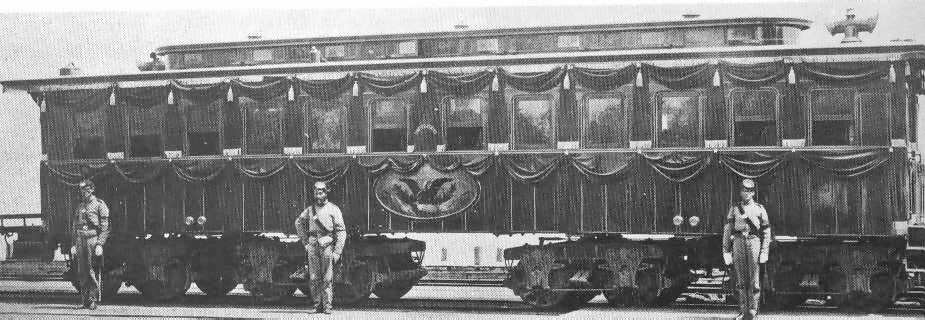

The funeral car that carried the body of President Lincoln from Washington, D.C., to his final resting place in Illinois.