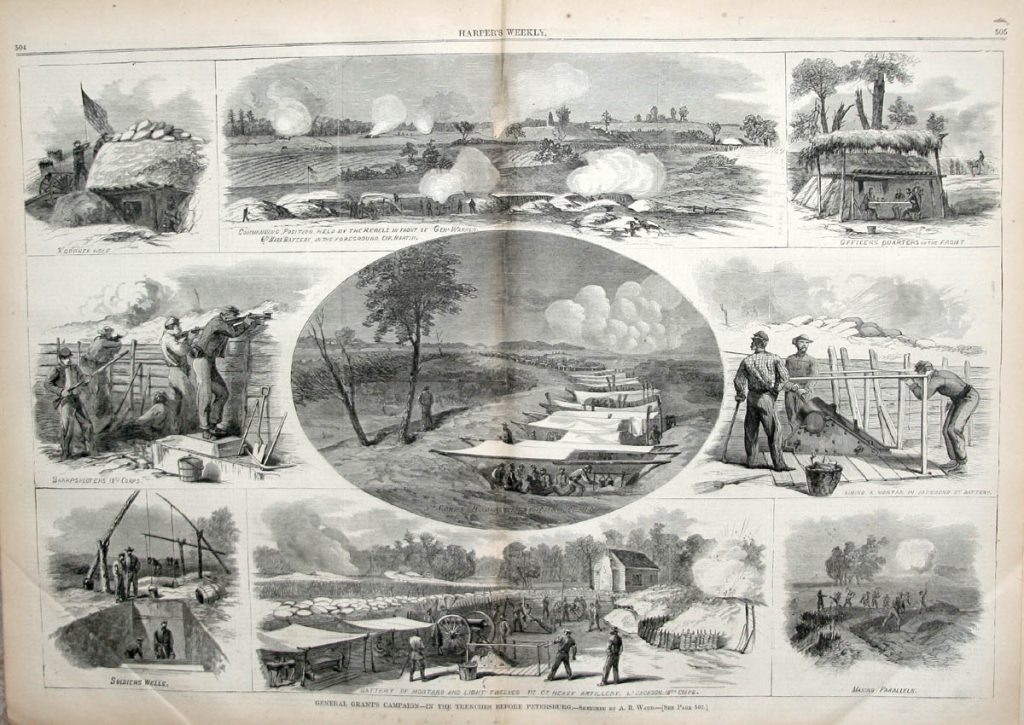

Civil War: August 1864, in the trenches at Petersburg

By Sandy Vasko

When speaking about great battles of the Civil War, many names come to mind, such as Gettysburg. Rarely does anyone speak about the Siege of Petersburg. But to the 39th Illinois Voluntary Infantry, Petersburg was akin to hell, and the methods used there, lasted until WWI.

Petersburg, Virginia, was the focal point of the Confederate supply lines to Richmond. In an attempt to cut off the supplies reaching Lee’s army, the North laid siege to Petersburg for 9 months, finally breaking through in March of 1865. The 39th was there starting in June of 1864.

On August 14th, they were moved to a place named Deep Bottom, and on the 16th, they were ordered to charge the works at Deep Run at the point of the bayonet. George Woodruff in his book, “Will County in the Civil War,” describes what happened next:

“On the 16th the brigade was ordered to charge the works at Deep Run at the point of the bayonet. The assault was made by the brigade most gallantly, but it was met by a resistance as stubborn and fierce. Even after the assaulting column had mounted the works, the enemy maintained a hand-to-hand fight.

“But success at length crowned our brave boys, and the lines of the enemy were broken, and a large number of prisoners captured. But it was at a fearful expense. In perhaps fifteen minutes’ time, the

39th lost 64 men, and came out of the encounter with only two of the officers left on duty that appeared on a roster of 28, when they left Washington in the spring.

“During this action, a private of Co. G, Henry M. Hardenburg, encountered the color sergeant of an Alabama regiment, when a desperate conflict took place for the colors. After a sharp struggle of some minutes’ duration, Hardenburg was the victor, having dispatched the rebel sergeant, and captured his colors, not, however, without receiving divers wounds himself.

“He presented the captured colors to Gen. Birney, commanding the corps. General Butler, on hearing of the affair, promoted him to a lieutenancy in a colored regiment. But he did not live long enough to assume the position, as he was himself killed at Petersburg, two days before the commission arrived.

“The entire loss in this engagement in the 39th was 104 in killed, wounded and missing.

“In the latter part of August, the regiment went into the trenches in front of Petersburg, where it was on duty and under fire almost constantly, night and day.”

This was the first time trench warfare was used in battle, and it would continue to be used as a useful strategy through the First World War.

Note that a reward for private Hardenburg, newly promoted to lieutenancy, was to become an officer in a black regiment. Virginia had the highest population of slaves in the Confederacy, and the population around the Petersburg area was 50 percent black. Many of them slipped their bonds and volunteered to fight for the Union. Petersburg was the first battle that was fought by colored regiments to a significant degree.

Note that blacks were not allowed to become officers, as it was thought that they simply weren’t smart enough to command. In addition, it was thought that they were used to taking orders from white men and so would respond more readily. This notion carried through until WWII.

With losses like the ones the 39th suffered, new recruits were constantly needed. Lincoln had put out a call for 500,000 more men, but volunteers were harder and harder to find. On August 20th, the Will County Board of Supervisors met and voted a $200 (about $3,975 today) to anyone who would volunteer as a substitute before the draft was initiated.

However, even $200 was not enough of an incentive, and private brokers were needed to find substitutes, but for a much higher price. Cal Zarley, the well-known editor of the Joliet Signal and hater of the black race, was desperate to find a substitute. He paid $600 (about $11,900) for a substitute for himself, who ironically was black.

Woodruff says this about these substitutes: “At this time, too, as many, both black and white, who had gone as substitutes, did not prove very good soldiers, but embraced the first opportunity to desert in fact turned bounty-jumpers the government had to establish the rule, that the person who sent a substitute, should be responsible for his fidelity.”

The war seemed at a stalemate, an ever-hungry monster that ate the young and the brave at an alarming rate; it seemed to the weary folks of Will County that there was no end in sight. And in August 1864, they were right.

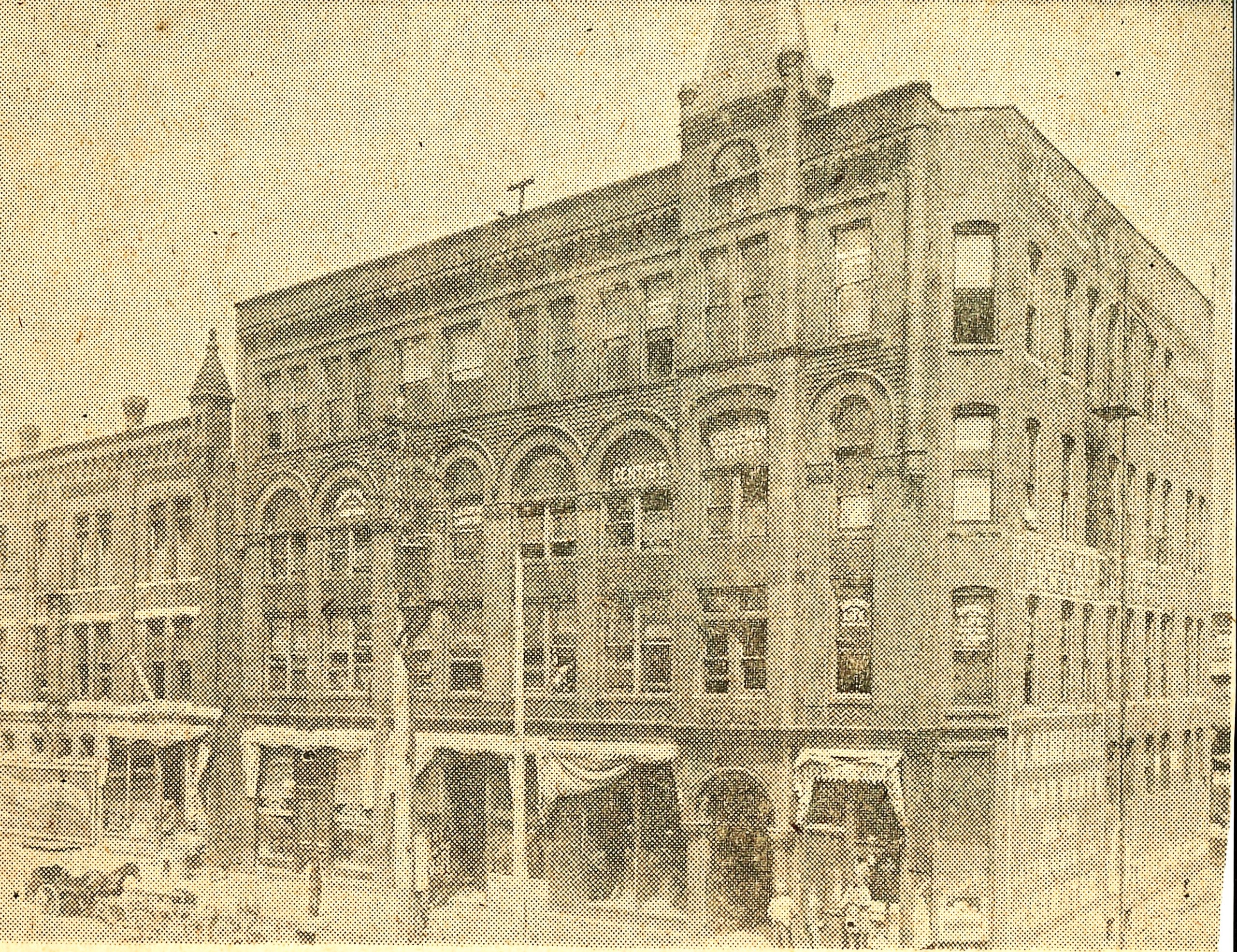

As the cooler winds of September 1864 blew across the nation, Will County could feel the draft. Not the one in the air, but the one that took place at the Provost Marshal’s office in the building known as Young’s Block in Joliet. The quota for soldiers had not been met and the draft drawings started on September 27th, 1864.

LaSalle County went first, but soon it was Will County’s turn. Ninety-four names were drawn, and of those, the first 47 were required to fill the quota. One of the names drawn was Alfred Rowley, Supervisor of Homer Township. But many of these never served, instead opting to pay a substitute to go instead of them. The price for substitutes immediately rose from $400 (about $7,950 today) to $1,500 ($29,750 today) a man.

With elections drawing nearer, the Democrats nominated George McClelland to run against Lincoln. They also started advocating a policy of compromise with the South. But those who had lost loved ones in the war saw that as a slap in the face.

A photo from an old newspaper showing the Young Block, located on Jefferson near the Rock Island tracks, where the draft office was located.