Civil War: June 1864 – Kennesaw Mountain takes a toll

By Sandy Vasko

Georgia in June can be a beautiful place. Not as nice as Will County, but the men of the 100th could not think of home. What they thought of was what lay before their eyes — Kennesaw Mountain.

During the first week of June, the boys of the 100th remained in their rifle pits, but very little action was taking place. In George Woodruff’s book, “Fifteen years Ago, Will County in the Civil War,” he writes of this time:

“The distance between the rifle pits of the two lines was about fifty yards, so that they could talk to each other, and during the last few days, the soldiers in them would enter into a truce on their own account, agreeing not to fire on each other for a certain length of time.

“About the 5th of June, the enemy did not answer to roll call, and we moved on again to near Ackworth, where we remained until the 10th.”

After some movement on the 11th of June, the 100th found themselves looking at Kennesaw Mountain. Woodruff describes it: “Looking to the front we could see on the right, Lost Mountain,

and on the left Kennesaw, the rebel lines reaching from one to the other, and beyond lay Marietta.

“Soon after noon we began to move forward, and during the afternoon orders came for our brigade to make a charge. The necessary preparations were made knapsacks, blankets, and everything that was not absolutely necessary, was piled up and left in charge of a guard, and every one braced himself up to do his duty.”

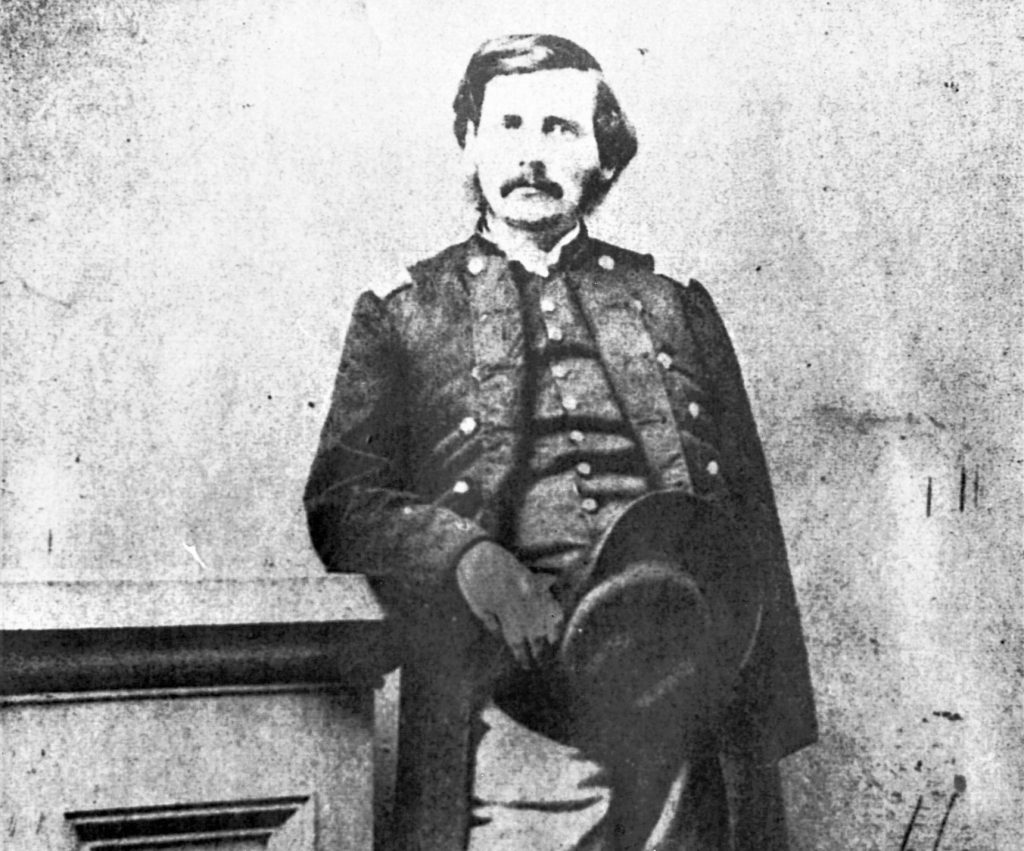

Col. Fredrick Bartleson, who had recently returned to the 100th after spending the winter in Libby Prison, requested to be placed at the front of the regiment during the upcoming battle. This cheered the men and they vowed to follow him anywhere, to hell if need be.

On the 18th of June, the 100th was ordered to relieve the 3rd Kentucky during the middle of the night. At 9 a.m. the next morning, the commanders of the 100th Illinois, 57th Indiana and the 26th Ohio, after consulting with each other, decided to charge the enemy works. This action was not ordered by headquarters, but nevertheless, they went ahead.

They were successful. Woodruff writes: “When the shouts of victory went up, the noise reached Newton, the division commander, who sent for Wagner, the brigade commander, and wanted to know what was up. Gen. Wagner replied that he couldn’t tell what his damned tigers were about. They were moving without orders, and he would have them court-martialed.

“But when they learned of the success of the movement they were satisfied. (In war more, even than in civil life, perhaps, success covers a multitude of sins). The affair was entirely impromptu, and so sudden and dashing that the rebs were taken by surprise. The 100th captured 14 prisoners and 1 lieutenant.”

The enemy played hide and seek until the morning of June 23rd. Woodruff continues the story: “Our record has now brought us to the 23d day of June, the day when we lost our gallant and well-beloved commander, Col. Bartleson. He was on duty as division officer of the day in charge of the skirmish line.

“While directing his line, the colonel was obliged to pass a point which was exposed to the enemy’s sharpshooters, and he was hit and killed instantaneously. The stretcher bearers of the 57th Ind., seeing him fall went to him at once, and finding him dead, carried the body back of a barn nearby, and sent us word.

“Our own bearers were immediately sent out after the body and brought it in, and the regiment then passed in review by the body to take their last hasty look at one they had so loved and honored.

The body was then carried back to the rear, to a spot which had been appropriated as a division cemetery. There were no other casualties in the regiment that day.

“The remains of Col. Bartleson was received in this city on the 1st inst., and conveyed to Young’s Hall by the Knight Templars, of which ancient Order he was a devoted member, and on the following day it was borne thence to his late residence on Broadway.

‘The funeral took place on Sunday the 31st, at 2 p.m. The body was conveyed to the Congregational Church by Knight Templars, where a most eloquent, appropriate and affecting eulogy was delivered by the Rev. John Kidd, pastor of the church.

“At the conclusion of the ceremonies at the church; an imposing procession, consisting of the different Orders of Free Masons of Joliet, Lockport, Wilmington, Channahon and other towns of the county, the city authorities, the fire companies of the city, the Fenian Brothers, and citizens was formed on Ottawa street. On a given signal, the vast cortege, accompanied by the Joliet Coronet Band, commenced its slow and solemn march to Oakwood Cemetery a mile and a half East of the city.

“On arriving at the grave, the solemn Masonic obsequies over the dead were performed, and the body was lowered to its last resting place, no more to be disturbed by the roar of artillery or the tread of belligerent columns, when the immense multitude that had assembled to pay respect to the deceased departed in silence for their homes.”

We now come to the “assault on Kennesaw Mountain” on June 27th. The charge was repulsed, the enemy was too firmly entrenched, and the carnage was horrific. Maj. Hammond and Capt. Rodney Bowen rallied 150 men at a depression in the hill and might have been able to hold it if the entrenching tools were sent forward as requested. Their requests went ignored, and they were ordered in.

The way back exposed them to a rain of fire, and when they returned the regimental commanders were astonished, thinking all had been killed and the colors captured. Three good men were killed, 16 injured, and 7 slightly wounded.

During July of 1864, the summer heat weighed heavily on everyone, but none felt it more that the 100th Illinois Volunteer Regiment. The loss of their beloved Col. Bartleson also weighed heavily on them, but there was no time to stop and reflect. The war went on, and so did they.

Col. Bartleson’s grave marker at Oakwood Cemetery