The spy among us, Henri Le Caron

By Sandy Vasko

Last time, we read about the real Henri Le Caron and his double life. We continue with his incredible story:

In the late Joseph Clark’s paper, “The Spy That Came in from the Coalfield,” Clark writes, “Henri Le Caron was introduced to Lockport, Will County, by Dr. Charles Bacon. He had met Dr. Bacon while nursing a battle wound in Camp Johnsonville, Tennessee, a Union Hospital where Bacon was the regimental surgeon. Bacon was originally a captain and founder of C Company of the 100th Illinois US infantry based in Lockport. Le Caron, at the time in the 13th Regular U. S. Colored Cavalry, must have conversed with Dr. Bacon about medicine as a profession for Le Caron became his student.

“A further person of influence on Henri and his move to Will County was Scottish born William Dougall. Dougall was a captain in the 13th Colored Cavalry, the same unit where Le Caron was a lieutenant. Dougall would also study medicine with Dr. Bacon, eventually working at the Joliet State Penitentiary as a physician in the 1880s succeeding Dr. Bacon. Bacon held the position from the first of July, 1868, until July 15, 1874. Le Caron and Dougall attended the Chicago Medical College about same time.”

The above is a true representation of what Le Caron was doing in the early 1870. But in a bizarre twist to his story, Dr. Leslie Hannawalt from Wayne State University wrote a book called “Body Snatching in the Midwest,” and named Le Caron as one of those horrible men. She wrote, “On January 30, 1872, Dr. Henri Le Caron, who had graduated from the Detroit Medical College, was captured in Toledo as the leader of a gang of body snatchers.”

And later in the book, “In 1878, he was charged with exhuming two bodies in Toledo and shipping them to Ann Arbor. Le Caron, then using his alias as ‘Dr. Charles O. Morton’ complained of illness soon after his arrest. When examined by physicians, his body was found covered with eruptions. He was diagnosed as small pox and was sent to the Pest House. Shortly thereafter, he made his escape.”

As a follow up to this, I got a call at the Will County Museum quoting the above and also claiming that Le Caron sold the bodies from the Diamond Mine Disaster. I had to tell the man that after 60 days underground, there was not much of a body left to sell, and that there were more than 1 person and up to 10 surrounding the bodies from the time when they were brought up until they were put in the ground. The gentleman hung up on me.

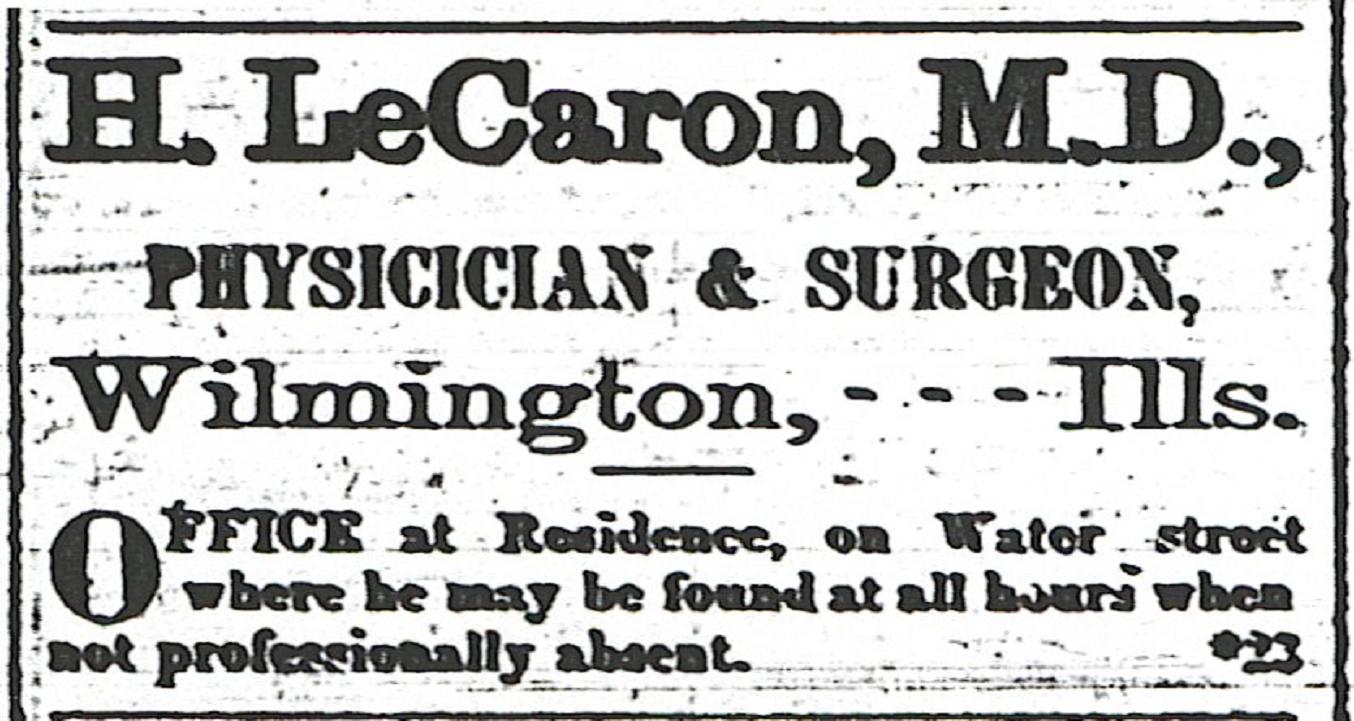

Dr. Le Caron was mentioned in local newspapers during the above mentioned time period, and so I can prove that while he was indeed doing something illegal, i.e. spying, he was not a body snatcher.

The Republican party of Will County had nominated Le Caron for the State Legislature, and the vote was hotly contested. The outlying townships all went for Le Caron, but in Joliet, where the majority of votes were, he was not trusted. Even though he was French, he seemed to always side with the Irish. And the Irish, as everyone knew, were drunks and trouble makers. The election was close, but Le Caron was defeated.

It was also at this time that Irish revolutionaries, long on politics, but short on money, were combing the U.S.-speaking for the rights of the Irish and gathering money for the cause. Societies like the Land League and Clan na Gael sprang up to bolster the coffers of the revolutionaries back in Ireland. Le Caron quickly weaseled his way to the very top of these groups.

He not only joined them, but also pushed them to the very extreme. In 1881, a convention was held at the Palmer House in Chicago for the Clan na Gael. Excitement ran high, and when the vote came at the end, all the delegates voted for dynamite instead of talk. LeCaron was there, urging them on to violence and mayhem.

It was then that suspicions were first aroused about Henri. Somehow secret plans made at the convention were leaked to the press. Henri was accused, but managed to deflect the accusations, and the matter was let drop.

Meanwhile, Le Caron went about his professional work as well, stumping the state for a pharmacy bill, which would regulate how drugs were given out to the public. This may have been his greatest contribution. At the time licensing was not required; anyone could set up a pharmacy. In addition to drugs like cocaine, laudanum, morphine and alcohol were sold freely. Many died of overdoses, and many more became drug addicts.

It was also at this time Le Caron took a trip to Europe. He went to Paris, London and visited the Irish countryside. While in England, Le Caron also managed to report all he had found out about the Irish to the British Parliament. They sent him back, well pleased with his work. And if it hadn’t been for one nosy Braidwood man, he may never have been discovered.

Robert Huston became Postmaster of Braidwood in 1882. And while Postmasters were not supposed to read other people’s mail, Huston noticed something peculiar. Le Caron was receiving monthly money orders and bank drafts, all drawn on the Bank of England. This put up a red flag, why was the head of the local Irish group receiving money from the enemy? He quickly spread the word.

Once again, Le Caron lied. He claimed that he owned an estate in England, and this was the profits from that investment. Some believed him; some did not.

Eventually, things got too hot for him in Braidwood. He moved on to Chicago, but the rumors followed him. He and his family returned to England where he testified against Parnell. He died a short time later from lung disease.