Civil War: February 1864, going home at last

By Sandy Vasko

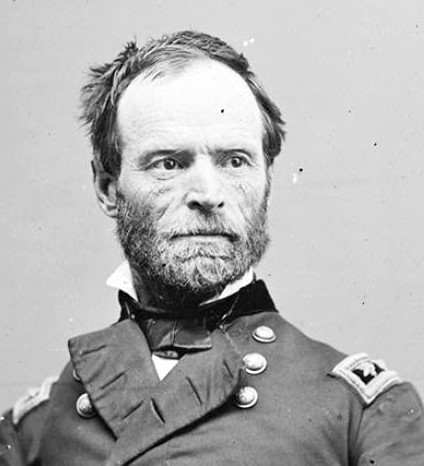

General William Tecumseh Sherman, who apparently did not own a comb.

Winter quarters were the rule for most Will County regiments in early 1864, but not the men of the 39th who had been stationed on Folly Island near Charleston. In his book Dr. Charles Clark, surgeon of the 39th, recalls why:

“During the time that we remained on the island, the regiment was induced to re-enlist for 3 years or the continuance of the war, with the exception of about 100 who preferred to remain in this department until the term of their service expired and then proceed home for good.

“Two large propellers had been assigned to carry us to New York, and the regiment was divided for the passage. The right wing of the regiment and the regiment staff took passage on the City of Bath, while the other wing took the Mary Boardman.

“We left the harbor at about 10 o’clock P.M. About 9 o’clock in the morning, we neared ‘Frying Pan shoals,’ and those on deck had their attention called to what was considered a school of porpoises disporting, but we were not quite certain in the matter, and went forward to the pilot-house to make inquiry.

“The man at the wheel did not know exactly what it was, at least he said so, but as we approached nearer and nearer, we became convinced that it was shoal water, and our conjectures and fears were more than realized in a moment more when the ship struck the bar with a dull, heavy thud which brought us to our knees.

“After striking, the ship careened over at an angle of 45 degrees, and we all rushed to the opposite side in the endeavor to balance her. The sea was calm and smooth when we struck, but there was evidence of an approaching storm in the light puffs of wind that occasionally reached us.

“Under the orders of the captain, we rushed from side to side of the ship and full steam was put upon the reversed propeller. The wind continued to freshen and the waves became quite respectable in size, and we began to feel a little uneasy at the prospect, when all at once, at the expiration of the third hour, the cry came, ‘She moves! She moves!!’

“Such a glad shout of thanksgiving as went up from the hearts of 250 war-worn soldiers never was listened to before or since.

“The captain of our vessel was an Englishman and had, in conversation, expressed his sympathy for the South, and when we struck the bar, we did not know but what it was a pre-concerted plan to wreck us. We held a short consultation and came to the conclusion that, if he did not make the proper endeavor to extricate the vessel we would, before compelled to leave the vessel, hang him and his officers to the yard-arm.

“Our trip was destined to be an eventful one, for in a short time after the late disaster, we discovered the ship on fire around the smokestack on the second deck, but a few pails of water sufficed to extinguish it.

“The storm came on apace; as we rounded Cape Hatteras it seemed to reach its greatest fury and it became impossible to keep a footing. The vessel rolled fearfully, and at times, we had some fears of completely rolling over.

“Later in the day, another and more grievous calamity befell some of the men of Company I, who were located in the vicinity of some huge water-casks which broke away from their lashings and came like an avalanche upon them. Six men were seriously injured-broken ribs, arms and collar bones, and it was with the utmost difficulty that we got them aft into the cabin where their injuries could be attended to.”

The 39th finally reached New York, and from there to on to Chicago by rail. On the 28th of February, they received orders to go back to the front and to another long summer of war.

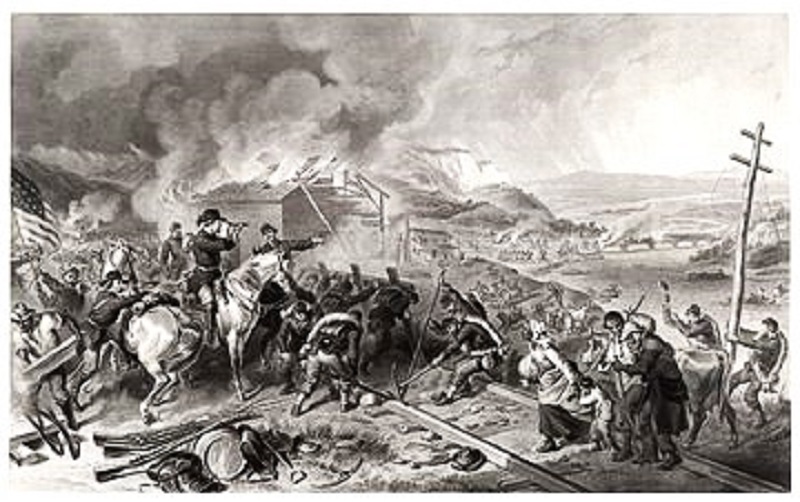

The 20th Illinois Infantry was another regiment that did not see winter quarters. They were with Sherman on his famous march to the sea, burning a swath across the south. They were the first to volunteer for the war and three long years later, they were still fighting.

In a journal entry, one unnamed man of the 20th wrote: “Thus, from Feb. 3d to March 4th, we had marched 375 miles, captured and burned the towns of Clinton, Jackson, Brandon, Decatur, Hillsboro, Chunkey Station, Meridian, Enterprise, Forest, Quitman, Canton and Brownsville; captured and burned 35 locomotives and 125 cars; and killed about 400 rebs, wounded 800 more, and took 800 prisoners.

“We had captured 2,000 horses and mules, and brought in with us 10,000 contrabands (former slaves) of all ages, sizes, colors, sexes and shapes; in all kinds of conveyances from the great plantation wagon, crammed full of woolly heads, down to the smallest jackass, loaded down with a big wench on her pack of movables. Our contraband train was a sight to behold, worth more than any street show that Barnum ever organized.

“We had destroyed more than 150 miles of R. R., burned every R. R. building on the route, and every cotton gin, mill and public house, and some private ones. Long, long will the people remember the visit of Sherman’s army, and its marks will not soon be obliterated from the region.”

Only 197 of the original 600 men were left in the 20th, and now, at long last, they were given a furlough home. This reward came because a majority of them had reenlisted for the duration.

It was also at this time that news came that their old comrade, Col. Bartleson, had been released from Libby Prison and was going home, too.