The Diamond Coal Mine Disaster of 1883

By Sandy Vasko

February and floods, they go together. The recent flooding in Wilmington proves it yet again. All across Will County, we were all holding our breath as puddles became small lakes, and ditches became creeks. This is flooding we can see, but what about flooding that we can’t see, like underground?

On Feb. 16, 1883, flooding underground in the small community of Diamond, just outside Will County, resulted in disaster.

The community of Diamond was not much bigger then than it is now. Its main focus was the coalmine belonging to the Wilmington Coal Association. It was a typical mine for the region. It was built first by digging a shaft 75 feet deep into the ground; then two main galleries were run nearly parallel to the earth and about 75 feet below it.

From these main galleries, narrow spurs or gangways were dug out in various directions depending on the location of the veins of coal. State law required escape passages two-and one-half feet high by four feet wide be maintained through out the mine, and the company had fully complied.

The surface of the ground was pockmarked with sloughs where water would not only stand, but running veins of water just underground, created dangerous quicksand over the stunted prairie. Occasionally the underground coal shafts would rise quite near the surface, sometimes directly under one of these pockets of standing water. At this time of year, melting snows and heavy rain had made the entire prairie a shallow sea.

The first person to notice anything wrong in the mine was the pump man, located at the bottom of the shaft, and whose duty it was to keep water out of the shaft. He found water rising rapidly, and thinking that it was for lack of steam power in the engine, which pumped the water to the surface, he went up top to call for more. When he came back down he was astonished to find the water waist high.

It seems that a miner digging directly under a slough had gotten too close to the surface, and a cave-in occurred directly under a sinkhole that had caved in three years before. The water rushed in with tremendous force, quickly filling one gangway after another, cutting off escape to the central shaft.

There was little time to give the alarm, and less than an hour after the break, every avenue of escape was cut off. Because escape tunnels were only two-and-one-half feet high, miners had to crawl against the rushing water, slipping, sliding and fighting the bone-chilling ice water.

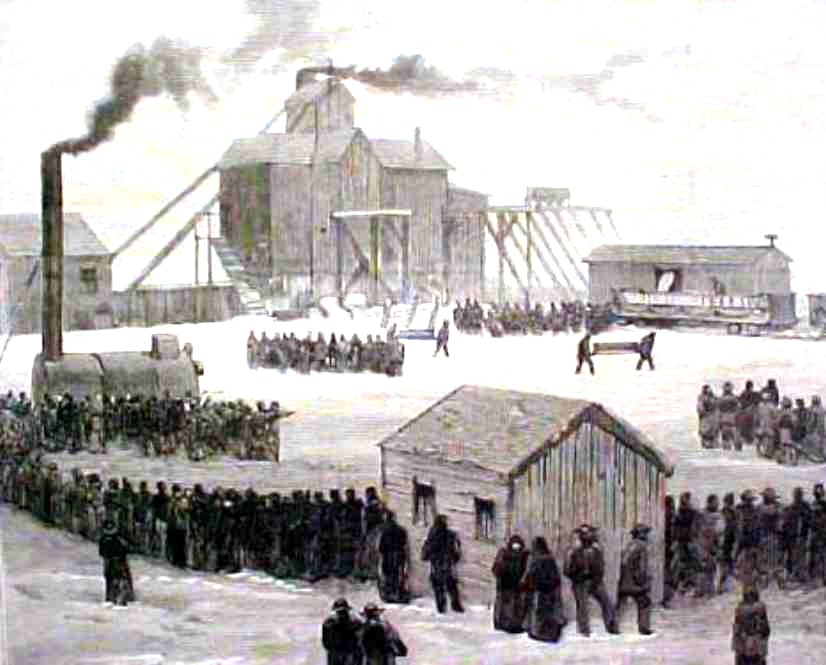

The big whistles of the engines were sounded three times, the signal for disaster, and within a few minutes, over 400 distracted women and children gathered around the mine, waiting for their loved ones to come out of that deathtrap. But most were disappointed, only 20 men got out alive, leaving over 75 people trapped like rats in a watery grave.

The stories of near death and heroics were many. Pat Redmond and his two sons reached the escape shaft when the younger one stumbled. Pat had his foot on the cage, but turned back to save his boy, and father and son were swept away to a gloomy death.

A man, with the body of his dead child, climbed up the winding stairs of the airshaft. He was ascending the last ladder, with his wife bending over the shaft to greet him when he lost his hold. Still clinging to the corpse, he fell to the bottom never to be seen again. The cool-headed men above ground had all they could do to stop miners from going down in cages to help their fellows. All who went down were lost.

The victims ranged in age from 13 to 54 and represented eight nationalities. The surviving families faced a glum future. There was no worker’s compensation or Social Security. Many of the widows did not even speak English, having arrived in this country only months before the tragedy. This was especially true for the German and Polish families.

A committee was formed to raise money, and every miner then working on the prairie contributed one day’s wages to the relief fund, a day’s wages in the mine being about $2.50 ($83 today). Across the country the story spread, eventually making it to New York, where a large amount of money was raised and sent to help the survivors.

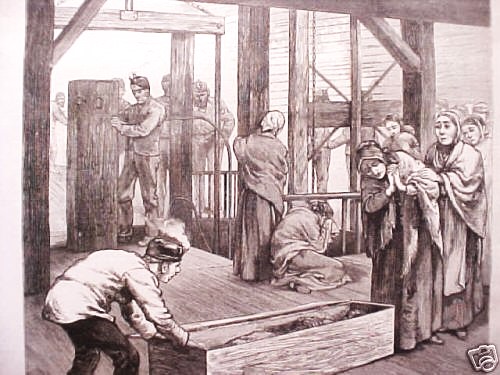

An attempt was made to pump the water out of the mine to recover the bodies, 22 were found, and eventually 19 were identified. But the conditions below were overwhelming, water continued to come in and many of the shafts had caved in. It was eventually given up, and the mine became the final resting place for many.

As soon as the news spread that bodies were being recovered, smoke of a train engine could be seen coming across the prairie, and scores of people flocked to the dead house to catch a glimpse of the scene. The bodies were loaded on flat cars and taken back to Braidwood.

A brawny Scotchman and a Yorkshire lad were in charge, and the former did not want to open the coffins for the crowd to see because of the advanced deterioration of the bodies. But the women cried out to have them opened, hoping to find the body of their loved ones and find closure. It was done.

Burials were immediate, and life in the mines on the prairie went on. But life had changed for many.

A woman identifies the body of one of the victims of the mine collapse in this sketch from Harper’s Illustrated.