Civil War: August of 1863, no end in sight

By Sandy Vasko

After the Union victory at Vicksburg, there was a hope that it would cripple the South, and the war would soon be over. But the sweet taste of victory soon soured, and it was apparent there was much more fighting to be done.

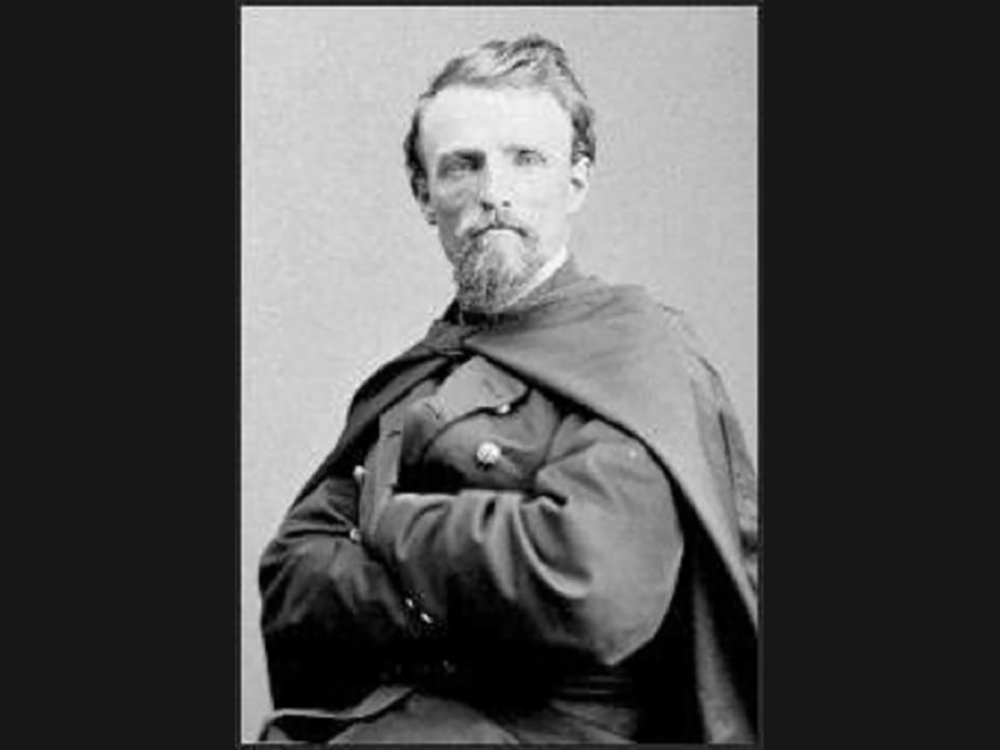

The 100th was stationed in Tennessee under the command of Col. Buell. On August 16, they were ordered to move.

“The day was extremely hot, and starting on a fast walk, many were soon used up, being nearly sun struck. At 4:30, they were at the foot of the mountain, 11 miles from Hillsboro. All took a good look at its steep and rugged sides, and dreaded the morrow’s work, past experience having taught them that it would be no easy job to get the train up the mountain. The order for the next day was given out — reveille at 3, march at 4 o’clock.

“The next day more than fulfilled their expectations. The regiment was marched part way up the mountain, stacked arms, and turned in to work again reinforcing the mules, pushing and pulling at the wagons.

“The road was full of sharp turns, and the ascent at times almost perpendicular. The wagons had to be partially unloaded, and two trips made for each load. The first one was not concluded before midnight. The regiment was then allowed to rest, and most of them fell asleep in their tracks, when one of those strange and unaccountable panics broke out, the origin of which, at the time, no one could tell. “It started, no one could tell why, where, or how, but all at once, the men found themselves running around in the dark, stumbling over the rocks and each other, and for a few moments, all was confusion and apprehension of something, they knew not what.

“Some were under the impression that the returning teams had run away, and they were in danger of being run over. But the scare soon ended, with nobody hurt. It was afterwards found that some mule driver ran over a soldier sleeping in the road, who started up from a sound sleep, half awake, and made such an outcry as to arouse the rest and create the panic.”

The ascent was completed by half-past nine o’clock the next morning, and a rest was given until one o’clock p.m. In getting up the mountain, the boys lost and had to throw away much of their baggage. Headquarters mess lost their provision box. The colonel lost his favorite camp chair. The adjutant and major lost their cots, and all, their tents.

“About the seventh day, rations began to give out, and the boys were put on three-fourths allowance, but they would not stay put, and occasionally a gun was heard to go off, and soon after two soldiers would be seen coming into camp, the one in front with a pig on his shoulder, and the other behind him with fixed bayonet, as if taking him to the provost.”

As September of 1863 dawned at the front, the men of the 100th were on the move. They took advantage of the scenery and local attractions along the way. Many of them explored caves for the first time in their lives and described them as “quite the most beautiful thing.”

Others availed themselves of the opportunity to stand in three states at one time, going to the three-footed monument that stood at the point where Georgia, Alabama and Tennessee touch each other.

On the night of the 6th, they found themselves 7 miles from Chattanooga, in sight of Lookout Mountain and the signal stations of the enemy. The 11th found them at Gordon’s Mills.

Here we must look to George Woodruff in his “The Civil War Year’s in Will County” for a description of the Battle of Chickamauga:

“As we have seen, by a series of masterly movements on the part of Rosecrans, he had maneuvered Bragg out of the stronghold of Chattanooga, and where he awaited reinforcements from Longstreet, which, unfortunately for the army of Rosecrans, came in time and in force sufficient to break the Union army into pieces, and to send its broken ranks, after a brave resistance, back to Chattanooga; leaving many a brave soldier dead or wounded on the field, and in the hands of the enemy. In its result, this battle was about equally fatal to both rebel and Union armies, and to the reputation of their several commanders.”

The 100th stayed at Gordon’s mills until the real fighting began on the 18th, with a fake attack which covered the real troop movement to flank the Union forces.

Around 3 p.m. on the 19th the 100th moved in. “Our brigade was accordingly formed behind the 8th Ind. and 6th Ohio batteries, and commenced to advance in two lines, the 100th and the 26th Ohio in front.

“But almost as soon as they had got into position, the troops in front gave way, and came rushing through the lines of our division in wild confusion, a battery running over our men, killing one and wounding several others, and compelling the brigade to fall back also, across a narrow field to the edge of the wood where it reformed.

“In crossing this field, they were under a raking fire of the enemy, and suffered considerable loss. The regiment having reformed its lines, word came to Col. Bartleson that Gen. Wood wanted the 100th to make a bayonet charge on the advancing enemy.

“The boys responded with a cheer, and charging drove the rebels back across the field into the wood where they rallied, and our regiment endured a short and murderous fire. The enemy then rallied and made a charge upon our troops in turn, and the regiment on the left of the 100th gave way.

“The 100th maintained its ground until all the troops on both its right and left had given way, and were about to be surrounded, and were getting a sharp fire on either flank as well as in front, when they fell back again, leaving many dead and wounded on the field. Again, our brigade rallied and drove the enemy in turn, and again’ retreated, and again rallied.”

Night came on, and the weary men got what rest they could, while Surgeon Woodruff and his men scoured the battle field for the dead and wounded.

We leave the men at rest, until next time.