Put ‘Em Up! Prize fighting, illegal and popular

By Sandy Vasko

The why of it is unknown, but everyone loves a good fight. Whether it’s in the movies or in the news, we want to see it.

It is no wonder, then, that it became a business, or some say a sport, and Braidwood in Will County was in the forefront of that developing sport.

Bare-knuckle prize fighting had its beginning in the British Isles, primarily in England and Scotland, in the early 1800s, but it was frowned upon by high society, and so it remained illegal until the 1900s.

In the U.S., bare-knuckle boxing arrived with the earliest immigrant to our shores in the 1600s. By the early 1800s, boxing matches on the East Coast were common, though still illegal. Boxing gloves were not used; it was legal to continue to hit a man when he was down, and the match continued until one man gave up or was unconscious.

Boxing matches usually ran 75 rounds or more and were held in out of the way places to lessen the chances of being arrested by the local police.

The first mention of this sport comes on Sept. 6, 1878, when we read in the Wilmington Advocate: “Morris – Some tramp from Braidwood has visited Mazon twice lately for the purpose of getting up a prize fight, but we are happy to state that our Mazon boys have too much self-respect to have anything to do with so disgraceful an affair as a prize fight.”

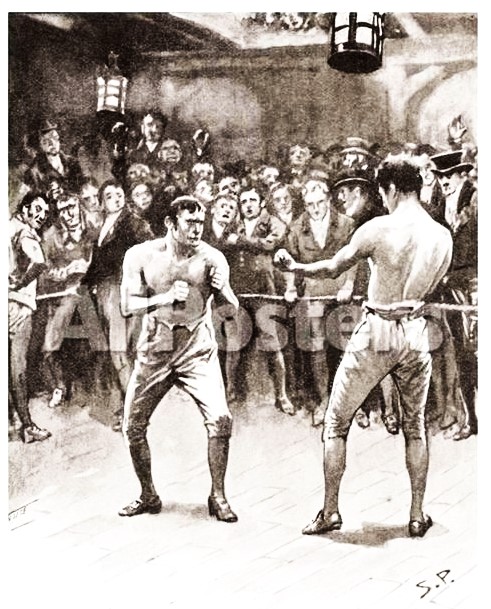

Despite the Wilmington editor’s attitude toward the sport, it continued to draw crowds. The following is a description of an organized match in August of 1885:

“The prize fight between Mulvey and Patterson, of Braceville, near that place on Monday morning was described by the Joliet daily papers as a very sanguinary affair, and was made to appear much more sensational than the facts in the case warrant. From what we can learn from eye-witnesses, the contest was for $200 a side, and it began at 6:15 on Monday morning at a point just over the Kankakee county boundary line.

“Mulvey is an Irishman, of about 160 pounds weight, while his opponent, Patterson, is a Scotchman, perhaps 15 pounds heavier. The men wore light boxing gloves, and the fight was more of a catch-and-throw wrestle than one of hard hitting.

“The battle lasted two hours and fifty minutes, and was witnessed by less than 300 persons, so quietly were the arrangements planned. It was evident from the fiftieth round that Mulvey was the better man in the contest. The number of rounds fought numbered 149, though some assert that the figure should be 126. Mulvey was ‘downed’ eight or ten times only, we are assured, during the fight.

“As to the stories of blood and gore flooding the prairie, it is all bosh. When the fight was concluded Mulvey had a very slight cut on the right cheek, and aside from that there were no wounds visible, other than bruised swellings.

“The ‘scrap’ was arranged according to London prize ring rules – one minute to each round, and one-half minute rest. But little science was displayed, the test savoring more of endurance than any other characteristic.

“It is true that officers of the law from both Braceville and Braidwood witnessed the fight, but it is claimed that they were not present in their official capacities. At the close of the combat Mulvey, quite fresh even yet and flushed with victory, leaped triumphantly into the air and then took up a collection for his plucky antagonist. The latter is said to be confined to his bed yet, although Mulvey attended the Foresters’ picnic on the day following that of the ‘mill.’”

Soon these matches were advertised out in the open, challenging the authorities to act. And the whole idea of a boxing match had changed so much that the fights took on a “party” quality to them.

We read in September of 1885: “Boxing exhibitions are billed for Braceville, Sept. 18th, between Adam Patterson and George Mulvey; Coal City, Sept. 19th, George Mulvey and Thos. Crawford; Braidwood, Sept. 21st, Wm. Patterson and George Mulvey. The entertainment will consist of boxing, wrestling, singing, dancing, etc.”

The following year, 1886 Mulvey and Patterson were still holding exhibitions. We read: “Owing to the fire in Braceville, the boxing match between Wm. Patterson and George Mulvey, advertised for Tuesday, is declared ‘off’ for the present. Mr. P. has something else to think of.”

And “There has been some talk of a boxing match here on Sunday between Chas. Lomasney, of Streator, and Geo. Mulvey, of Braidwood, for big money.”

Mulvey’s local matches always went well for him, and so he went on to be a professional heavy weight prizefighter, ending his career being the “second” for other prizefighters from the area in matches all over the country.

Coal country was not the only place that had illicit matches. In August of 1896, we read in the NEWS: “Hugh Bolton, who ran such a bad saloon in Joliet, that the police had to practically run him out of town, and who now has a free rein in the little village of Minooka, is gathering around him a pretty tough crowd, or at least he is demoralizing the young men in that community to a very alarming extent.

“The latest exhibition is a prize fight that occurred at the old woolen mill in the town of Troy on the farm of Highway Commissioner John Kinney during the early hours of Sunday morning. A fellow by the name of Kimmy Korzlitz, or Jimmy the Kid, from St. Paul, was matched against George Myers, a farmer boy from the town of Seward, Kendall County, for $100 a side.

“It seems Bolton had the management of the entire affair and sold tickets at $1 to a few friends who wanted to see the mill. The crowd sneaked out of town late at night and arrived at the scene of the proposed breach of the peace after midnight. Mr. Kinney heard the racket and went out and protested that he did not want anything of that kind to occur on his premises, but he was helpless, having no means of reaching police or county officers.

“Soon a rope was stretched around inside the old mill and about 1 o’clock the pummeling began with what was alleged to be soft gloves. The fellows shook hands, stripped to the belt and began business. They pounded each other in the face and about the shoulders until the eyes of both were nearly swollen shut and their bodies bruised black and blue; and at the end of the thirteenth round the exhibition was closed by Bolton declaring the match a draw. The men did not observe the rules of such exhibitions very closely, for one fellow bit the other’s toe nearly off and otherwise maimed one of the man’s legs.

“There were about 100 in attendance at the mill. Among them were several from Joliet, one of the Binson’s being reported there. Evidently though it was a very select affair, for the citizens in the immediate vicinity knew very little about it and were not present. Those who were favored with an invitation declare it was a very tame exhibition of brutality. The men simply pounded one another until the crowd and they themselves were satisfied.”