Civil War: December 1862, no rest for the 100th

By Sandy Vasko

While the other Will County regiments were going into winter camp, the 100th, the latest Will County regiment to enter the fray, did not find rest. They were stationed in Tennessee. A few days before Christmas, the orders to march came through. Sickness and desertion had whittled it down to 600 men fit for duty.

On Christmas Eve, two days of rations were issued, the wagons repacked and sent to Nashville for storage, and the tents pitched, with orders to be ready to move at daylight on Christmas Day. Lying on the cold ground, thinking of a warm home and Christmases they have known, they wondered if they would ever make it back. Their mood was lightened as if by Christmas miracle, 13 boxes for the regiment arrived with things sent from home. Each had a taste of Christmas and a reminder that they were not forgotten.

Orders on Christmas Day were rescinded, and the day was spent quietly in camp. At 9 p.m. on the 26th, the army was finally underway. The 100th camped on the night of the 27th in a wood, in the rain, without any tents. The next morning, the men were called up at 5 o’clock and allowed to build fires and cook breakfast. By 9 a.m., they were on the move again.

Approaching the town of LaVergne, one shot from an artillery piece evoked no response. But when they came within musket range, the rebels came out from their concealment in the houses and opened fire.

The 100th moved half a mile over an open field, under a heavy fire without a waver. When within eighty yards, charged on the double quick with a Union yell, and quickly drove the enemy out of town. Gen. Haskell complimented the 100th, who were made up of mostly new recruits, by saying, “We are all one now, old soldiers and new.”

During the following march, the going was rough. They had to fight their way through cedar thickets. But while doing so, they encountered a great number of rabbits. The boys couldn’t resist taking pot shots at them, putting them into their haversacks for future meals. Gen. Haskell chided them saying they would be caught by the rebels with their muskets empty, but didn’t say much more and the practice continued.

About noon, it began to rain and the march was halted. While there, a squad of rebel cavalry came charging down the lane, a volley of shots brought them to a halt, and they held their hands up to surrender. One poor man who could not stop his horse in time came charging on and was shot in the abdomen and dragged through the Union camp. His horse was eventually shot, and he was helped into an old shed, and taken care of very tenderly until his death 36 hours later. There was regret in the whole camp that his intention to surrender was not understood until it was too late.

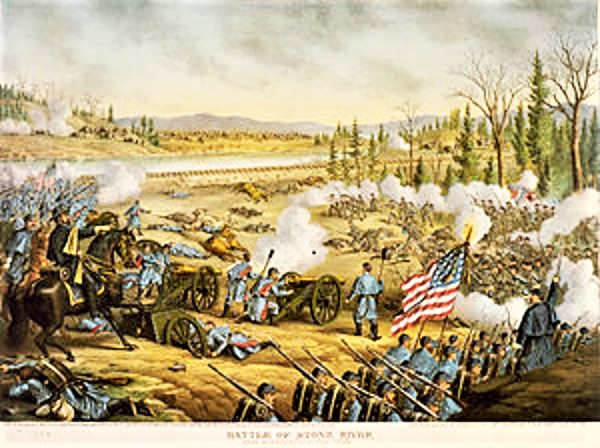

The 100th continued on until they found themselves on the banks of the Stone’s River on the fateful day of December 31, 1862, where they were to encounter the most horrific battle they had yet to see.

At home George Woodruff describes the scene: “And so peacefully, though anxiously, died out the closing hours of 1862 in Will County. In Washington – in the White House – alone in his office, sits a man on whom a nation’s eyes are fixed, reverently invoking the gracious favor of Almighty God upon the words which he has written – words which are destined to make the admiration of the world, and to strike the manacles from the limbs of four million slaves.” Lincoln would announce the Emancipation Proclamation on New Year’s Day, 1863.

On December 31st, 1862 the 100th was ordered to fall in at 9 a.m. in a cedar brake where they watched regiment after regiment move forward to the front, and soon saw the wounded going by in the other direction, leaning upon their fellow soldiers or being carried on a stretcher.

It wasn’t long before they were ordered forward, and then to lie down in a corn field. Soon the rebel batteries found them, and while changing positions, they came upon the 110th Illinois. The men exchanged cheers; Illinois would hold the line.

George Woodruff describes the moment this way: “After a little, a regiment in the rear is withdrawn, and the two, 100th and 110th, are left alone. They move forward to the edge of a cotton field. The enemy tried hard to dislodge them, but here they lie, hugging the earth, while they are treated to a brisk cannonade, and our own batteries are replying over them. What terrific music! The shrieking of shells, the thunder of artillery, the crash in the tree tops overhead; and here they lie, unable to do aught but hold on the most trying position in which men can be placed.

“The order to fall in comes again, but while doing so they expose themselves and 5 are killed, 30 wounded. They retreated and formed along a railroad. … But soon the boys saw the ‘butternut,’ (Rebels) and gave them a volley. They went over the fence, and down the hill, like a lot of sheep. Lieut. Mitchell, of Wilmington, here receives the wound which proved mortal three days after.

“They came on, a brigade eight rows deep, with fixed bayonets in splendid style. But our boys stood their ground, and gave them such a reception as made them falter. Their officers tried to rally and lead them on again, but our grape and canister mowed them down, and a few well-directed volleys of musketry finished their repulse. They turned and fled, our men pursuing them until getting into range of their artillery, they fell back to allow ours to reply, and thus was now kept up an artillery duel until darkness closed the scene.”

We will continue the Battle of Stone’s River next time, as we continue to look at Will County’s involvement in the Civil War.

This view shows a typical Civil War winter camp.