The one-legged sheriff of Will County

Spy Henri LeCaron

By Sandy Vasko

Hardy is a word that is usually used to describe early settlers in any part of the country. But in Robert Huston’s case, it just doesn’t say enough. Let’s look at the life of the one-legged Sheriff of Will County.

Robert Huston was born in New York City on August 7, 1844, to Irish immigrants Robert and Elizabeth Huston. His father was a weaver back in Ireland, but in New York, he scrambled to make a living. Searching for a better life, the Huston’s came west in 1850, settling on a farm near Gardner.

Despite his small size, only 5’ 4” at age 18, the younger Robert turned into a tireless farm worker. When the War Between the States broke out, he answered his country’s call, enlisting as a private in Company I, 58th Illinois Voluntary Infantry in 1862.

He fought at the battles of Fort Donelson and Pittsburg Landing in Tennessee. He was taken prisoner at Pittsburg Landing and taken south, but within a few months was released in a prisoner exchange and returned to his old regiment.

At the battle of Yellow Bayou in Louisiana, he was shot in the leg, causing it to have to be amputated. He was sent to the hospital in St. Louis where he remained for almost a year. He was mustered out in 1864 when he returned home to the family farm.

Not being fit any longer for heavy farm work, he tried teaching school at first, but found it was not for him. With $54 in his pocket, he moved to Braidwood, working at first for the coal companies as a weigher. He speculated in coal, buying low, selling high and made enough money at it to purchase a general store. He was a shrewd businessman and was soon one of the most prosperous men in town.

In April of 1879, he was elected Alderman of Braidwood, beating out about 20 other candidates. He dominated the city council proceedings, with the other Aldermen following behind, so much so that the Braidwood City Council became known as “Huston’s wax figures.” Three months later, his business smarts had people talking about making him Will County Treasurer, but he lost out to a more influential man from Joliet.

He was known as a man with a big heart. In 1880 we read: “Wm. Bell injured twice within two years, and unable to work in the mines, will dispose of his three horses, wagon, and buggy by raffle, on Tuesday eve, 26th, at John Walker’s place. Tickets, at 50 cents each, are on sale at Huston’s store, and elsewhere. Those who buy them will aid a worthy citizen.”

In 1882, Huston was appointed Postmaster of Braidwood. By this time, he was rich enough that he could purchase a building, move the post office into it, and open another general store to help “better serve the customer.”

We also know that he held the mortgage on the local newspaper, the Braidwood Republican, and when the paper fell behind in payments, Huston had the printing press and effects seized by the sheriff. He soon became the owner and publisher.

It was in his capacity as Postmaster that he was responsible for catching a British spy who was working with the Irish in Braidwood. And while Postmasters were not supposed read other people’s mail, Huston noticed something peculiar. Henri Le Caron, a popular local doctor, was receiving monthly money orders and bank drafts, all drawn on the Bank of England. This put up a red flag: Why was the head of the local Irish group receiving money from the enemy?

Huston quickly spread the word. The results were that the spy was soon unmasked, leaving Braidwood and the United States forever.

Despite his success financially, he remained a popular man. Folks honored him for his part in the war, and when services were held in 1885 to honor the passing of General Ulysses S. Grant, he served as President of the Day, and honoree. In 1885, he ran for Supervisor of Reed Township, but was defeated by John Kain. That didn’t deter him, and he quickly threw his hat in the ring for Sheriff of Will County on the Republican ticket.

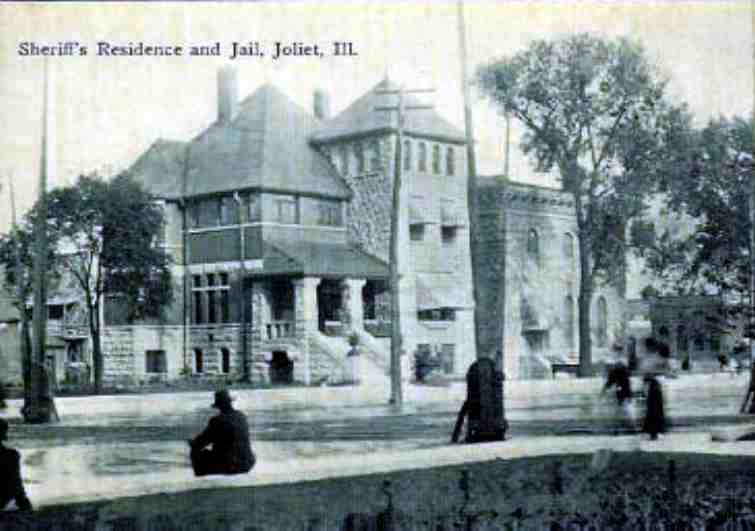

His popularity countywide assured him the election. In April of 1886, the little one-legged man from Braidwood was elected Sheriff. He moved into the Sheriff’s house, next to the jail in Joliet. He made his local boys deputies; they included Kelso Ballantine and Thomas Moore.

He was a no-nonsense sheriff, conforming to the letter of the law. In 1886, he made himself very unpopular in his hometown when he enforced the ban against prize fighting. We read on December 18, 1886, in the Wilmington Advocate: “Sheriff Huston has proclaimed that the advertised prize-fight between Daly, of St. Louis, and Myers, of Streator, to be held in Music Hall on Dec. 28, shall not take place within Will County. The ‘pugs’ named were to fight eight rounds for $500 a side.”

In an age when losing a limb usually meant a life of poverty, Robert Huston not only survived, but prospered by using his other God-given talents.