16 Tons, and What Do You Get? The Shaft

By Sandy Vasko

In the last few years, many have lost their jobs, many saw inflation take them into poverty, many saw hard times. These things happen, ask your grandmother about the Great Depression.

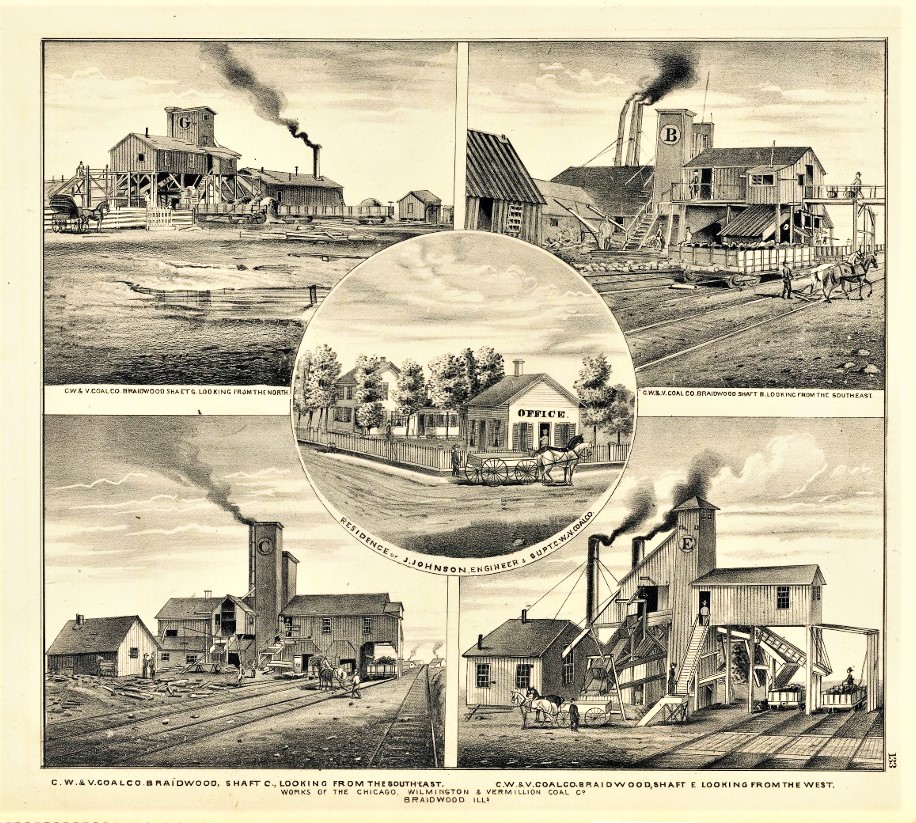

Today, we go back to another era of hard times in the southernmost part of Will County, Braidwood. It was a company town, and the coal companies owned everything, from the grocery store to the boarding house to the very land the houses were built on.

But you can’t keep people down forever. We start in 1874.

For months, the miners and coal companies had been in negotiations. The issue was of course wages. As it was, a miner could barely make ends meet.

By March of 1874, things had gone from bad to worse. The Braidwood paper says, “Large numbers are leaving for the West, the larger portion have fixed on Colorado as their future home. The hard times have led many, out of employment, to seek a new field of enterprise. Will Braidwood and Gardner be depopulated?”

The companies then announced that there would be a pay reduction. This was the last straw; the miners went on strike. The companies called in the Pinkerton’s to keep order. We read in June, “The miners’ strike in Braidwood still continues. The streets of the coal city are flooded with idle men and business is to some extent stagnated. Order and quiet prevail, and the Pinkerton police forces have nothing to do.”

The strike created wide attention. The Chicago Tribune wrote, “That 1,600 men, most of them with families dependent on them and forming a community of solidarity should voluntarily suspend work for an indefinite period in these times is a sufficiently striking to warrant the attention of the public. At present there is no indication that the miners will use force to drive off the men the companies may employ. They are certainly inclined to be peaceable. But who can tell what time and want may bring forth?”

The striking miners of Braidwood had learned to use the power of the press.

In August of 1874, the newspapers announced that the shafts were all open, and the strike was over, but the following week, they had to print a retraction. “We have some startling news from Braidwood. The C. & W. Company still holds out against the strikers it appears, and are working a force of some 300 so called blacklegs, and the number is being increased at frequent intervals. The ‘blacklegs’ now form a formidable force, and they are generally armed, it is said, for self-protection. It is true that Braidwood is quiet and orderly, but the fire is merely smoldering and is liable to be fanned into a blaze any day. Well-disposed men should use every endeavor looking toward a peaceful termination of what remains of the strike.”

At this point I need to define “blacklegs.” They are strike breakers, men who came to Braidwood to mine coal at whatever wage the company was willing to pay them. Across the country, other strikes had been broken by taking advantage of former slaves and poor white share croppers. Even though the war had been over for a decade; free slaves still could not find work in the war-ravaged South. When the coal company’s representative came to them and told them of work to be had in the North and free transportation for themselves and their families, they jumped at the chance and directly into the fire.

The tactic worked. The white miners went reluctantly back to work at the lower wages. The press wrote, “Strikes by any combines class of men hardly ever works to profit, but are sure losses to all concerned – Morris Herald”

Certainly, the miners felt like they had lost. And they took it out on those who had not held firm. We read on September 18, 1874, in the Wilmington Advocate, “Harvey H. Brown, of Braidwood, is said to be “spotted” by a certain clique of miners, some of whom have threatened even his life. Why? Simply because Brown saw fit to work for a living during the recent strike. Because he supported his family by honest labor for the C. & W. Company against the wishes of some of his manly, (?) reasonable (?) neighbors. Rather than to threaten violence, they should hide their faces in shame.”

In May of 1876, the coal companies announced a 20-cent reduction in the amount they would pay per ton of coal mined. By this time, the miners had an official union with Dan McLaughlin at its head. But not all miners were in the union, and that number included the black miners.

We read, “A mass meeting of non-union miners was held on Wednesday to consider the proposition, and though most of the shafts were idle, the attendance was not large. Resolutions were passed rejecting all propositions looking to a reduction. Daniel McLaughlin, president of the Miners’ National Union, and all other prominent union miners, kept aloof from the meeting, and took no part in the matter. The annual contracts take effect, we believe, on June1.”

As the strike loomed, the companies took a benevolent “Who me?” stance. We read, “From all accounts there is to be a change of program in Braidwood within a few weeks. It appears that the different coal companies have agreed upon a reduction in the prices paid for mining coal; the men have consulted and agreed not to accept the companies’ proposition. What then, a repetition of the last strike? Not much. The companies, says our informant, will hire no blacklegs or anything of the sort, but they will simply cancel their contracts and close up their mines. It is gratifying to know that the parties to the matter look at it coolly and philosophically.”

But just a week later we read, “Some 55 ‘blackleg’ miners were sent to Braidwood on Wednesday by the C & W Company. They are to receive $1 (about $28 today) per day and board. The practical miners would resume work at the same rate and produce double the amount of coal, but they would not contract to do so for one year. When the companies stop cutting each other’s throats through ruinous underbidding, then we shall hear of fewer strikes.”

The strike was again broken. The companies had won Round 2. Round 3 would be held in 1877, which is where I will meet you next time.