Our Rural Heritage: Civil War: Winter in the field, the 20th and the 39th

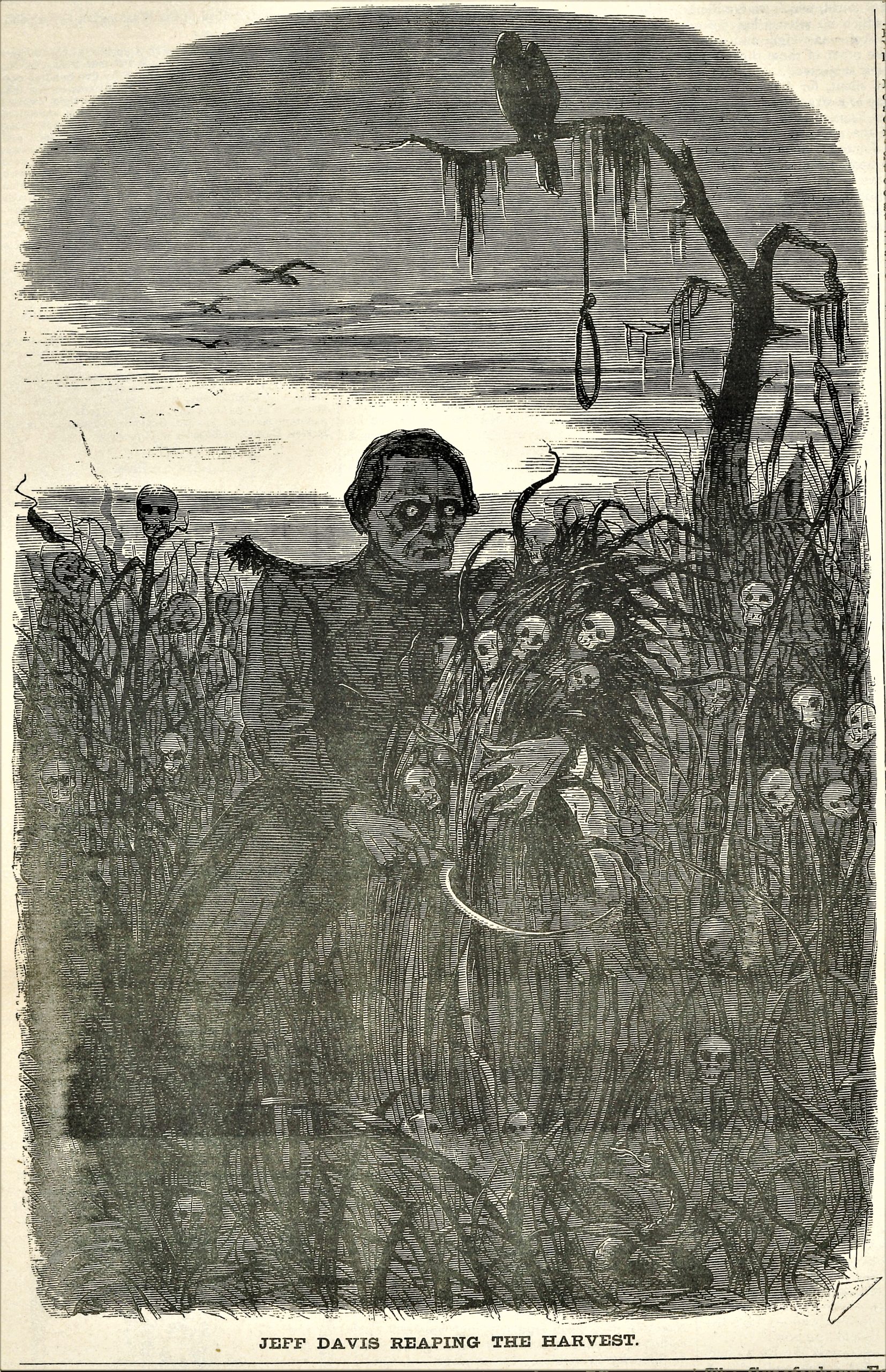

This depiction of Jeff Davis, President of the Confederacy, ran in a national newspaper called Harper’s Weekly during the time mentioned in this article.

By Sandy Vasko

The 20th, returned to Bird’s Point after the battle of Fredericktown on Oct. 31st, where they constructed log structures for their winter quarters and settled in. While there, they boys received visitors from Joliet. George Woodruff gives an account of it:

“Soon after the return of the 20th to Birds Point, it received a visit from some of its Joliet friends. Among them, Otis Hardy, Esq., and his two eldest daughters, and Mrs. Button, the wife of the worthy chaplain. Brother Hardy had heard that somehow hospital stores which had been forwarded to the boys from Joliet had failed to come to hand, and with his usual zeal and thoroughness he made it his business to investigate the matter.

“He accordingly looked up the stores in Cairo, and got them into the hospital. Not liking the looks of the hospital, (of which our boys had just taken possession,) he pulled off his coat, and with the assistance of the others, he thoroughly “policed” it, without waiting for orders or even a permit from headquarters. Some officials looked on astonished at so extra-judicial a proceeding, but I guess the inmates rather liked it.”

This points out the first-hand civilian participation in the war effort that was unprecedented before or since the Civil War. It was at this time, between battles, that in-fighting started to occur. The protracted stay at Bird’s Point with little to do made the 20th restless and old disagreements broke out again.

When the 20th was first mustered in, an election was held for Colonel, and a man elected whose name none of the locals had ever heard before. C. Carrall Marsh had been joined up by Governor Yates himself. His occupation is listed as corn merchant on his service record, but he seems to have had a lot of political influence.

There had been a question as to whether the fledgling regiment would be accepted into service. Regiments had been forming all over the state, and the competition was stiff. The men were eager to serve and so elected someone who could help them reach that end. As to the fitness of a merchant to lead a group of men in to battle, it would have to be tested later.

Now that Col. Marsh had been tested in battle, many found him lacking. A petition was circulated, signed by three-fourths of the officers and most of the enlisted men, demanding Col. Marsh resign. He refused to do so.

It was also at this time that Marsh denied Capt. Hildebrant leave to go to Cairo to meet his wife. Hildebrant went anyway. He was arrested and ordered to report to command. He did so several days later, and on his release, he was assigned to special services where he served as a scout.

Later, he was tried on disobedience and other charges. He was cleared of all charges, but for some reason, the papers failed to reach headquarters. Captain Hildebrant continued in special services until April 1862 when he rejoined the regiment as a private, carrying a musket. When the mistake was discovered, he was restored to his original rank.

New Year’s Day of 1862 found the 20th at Bird’s Point, Missouri. Many of the officers’ wives came down to Cairo to be with their husbands on that special day. Even Mrs. Grant held an “open house for officers under her husband’s command.

From the 20th, Mrs. Erwin, Mrs. Hildebrant, Mrs. Bartleson and Mrs. Goodwin held an all-day party for the officers, To be among women and all the touches of home, gave those whose wives could not make the trip, long for their families.

The privates also had their own special celebration. They held a masquerade, where all were dressed in strange clothing while they performed a burlesque drill, mounted on mules and using old stove pipes for cannon. Two of the men dressed up in women’s clothing and went round to the hospitals and camps performing “inspections”, giving little speeches, and making “impertinent” remarks that make the hospital wards shout with laughter. It was a day to remember, and for many, the last New Year’s Day they would ever see.

The rest of the month for the 20th was spent around Bird’s Point, going out on small skirmishes, but participating in no major battles.

The men of the 39th were in a much worse situation. On Dec. 31st, 1861 one young man named Tyler wrote home: “We are very comfortably situated here so far as winter quarters are concerned, but are quite destitute of good substantial clothing. Company E still have the same old uniforms in which we left Chicago, or I should say what is left of them. We are without socks, and none can be procured from the proper department at present. Lieut. Col. Osborn passed through here on his way to Cumberland to see about our new uniforms, but we have not yet learned the result of his mission. We hope he was successful, for if not we shall have to go to our bunks and cover up for the winter.”

They were camped in an area that was split as to Union/Confederate sympathies. Tyler writes, “Since we came here the people have suddenly become strongly Union in sentiment; but it is a very easy thing to point out the rebels, we find their flocks and herds untouched, their barns filled, their houses unsearched, and everything in good condition, while the houses of Union men are marked by the pale, care-worn faces of destitute women and children, whose husbands, fathers and sons have been driven from their homes, and their property seized and appropriated by the rebels. The mountains and valleys here abound in such homes as these, where the women and children are left to support themselves, while the male portion of the population are exiles from home.”

We leave the 39th here, on the brink of what would be their first taste of war. More to come.