Our rural heritage

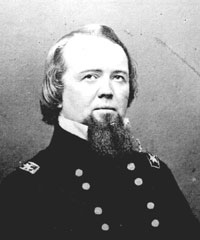

Brigadier General John Pope, after whom Camp Pope near Alton was named. He was considered a brilliant general, but after his stunning defeat at Manassas, he was sent to the Western front where he served his country well.

By Sandy Vasko

Last time we looked at the Civil War in Will County, we witnessed a wedding. But there is an end to everything, even a honeymoon. Time to depart came on June 19th.

The men received their pay and boarded the train to Alton. On the march to the depot, they were met by the Joliet Coronet Band and a huge gathering of friends, family and citizens in general who wanted to give what may be the last good-by to the brave fellows of the 20th Regiment.

At every station along the way, the men were greeted with good wishes and floral bouquet. At Monticello, every student at the female seminary there was at the station to greet the gallant men of the 20th.

They arrived at Alton at noon the next day. The plot of land assigned to them for their camp was less than ideal. It was full of hills and gullies, with stumps everywhere. There was no shade, and the water was not fit to have the name.

This great contrast with Camp Goddell back in Joliet, where huge oaks shaded them during the day and a spring supplied fresh clean water to all, brought home the fact that they were “in the army now, not behind a plow.” The area became known as Camp Pope and was shared with three other infantry regiments and a troop of cavalry.

It became clear that play time was over when, by accident, a young man of Company D was playing with his rifle and pulled the trigger of what he thought was an unloaded rifle. He shot two people, who survived, but were severely wounded and deformed. Both of them were later sent home. The Chaplain who viewed the event fainted away at the sight of blood, but later was found to be among the bravest of them all.

The food also was not like back home. They were issued wormy hard tack that had been in a warehouse since the Mexican War. It seemed less like food than like a building material. Some of the boys tried to remedy the situation by shooting a group of hogs that they claimed had gotten in their way. The hogs provided a great meal, however the officers took a dim view of it and made sure enough money was taken out of the rash soldier’s pay to compensate the farmer for his loss.

July of 1861 was a quiet time for the folks in Will County. The 20th regiment had departed and the grove recently occupied by them as Camp Goddell was quiet and serene. However, the citizens were not idle. In small towns across the county, men were organizing more companies to join the war effort.

In Wilmington, Capt. (later to be Major) Munn recruited what was to become Company A of the 39th Illinois Voluntary Infantry, and in Florence Township Captain Hooker organized what was to become Company E of that same regiment. Company E was also known as the Florence rifles. In Homer Township Amos Savage and Oscar Rudd organized part of what would become Company G.

But it wasn’t only the men who felt the call to war. Early on in Wilmington, the ladies organized a soldiers’ aid society to provide whatever the government did not. They held fairs and socials to raise money to buy uniforms, they knit socks and canned preserves, they wound bandages and bought bibles. Soon other towns did likewise.

As for the men of the 20th, they were still getting used to camp life at Alton. On the Fourth of July the entire brigade attended services and as a group retook the pledge to uphold the Union from all enemies.

On the 5th of July, the 20th was notified that they would be on the move, and on the 6th, they took steamers to the arsenal at St. Louis where they received their arms, equipment and clothing. Many of them were disappointed with the old arms they received. Old U.S. issued flintlock muskets, converted to percussion locks, were issued to them. Although these muskets were antiquated, they proved efficient and deadly, and many men kept them throughout the entire war.

St, Louis was a city that had as many southern sympathizers as northern. In one instance, the boys of the 20th were walking down the street when a group of rebel sympathizers in a livery stable shouted out, “Three cheers for Jeff Davis and the Southern confederacy!” That was the signal for a charge by the boys of the 20th, and the livery stable was cleared out in short order.

On the 10th of July the 20th once again boarded steamers – destination Cape Girardeau. On the same night they landed, a rebel provision train was spotted headed toward the southern lines. Col. Erwin of Will County asked for volunteers to capture it, but Col. Marsh countermanded the order, saying the men were too tired to go out that night.

Col. Erwin then asked for his home town boys from Will County to volunteer despite their fatigue. They returned back later that night, having captured seven loaded wagons, five yoke of oxen, four horses and eight prisoners. Twelve rebels managed to escape them.

The 20th was also responsible for holding an embargo on all river traffic, and succeeded in stopping the steamer Memphis containing a large supply of medicines hidden in private luggage that was destined for rebel troops.

Col. Jeff Thompson, known for his commando style raids in Missouri and Illinois. Capt. Hildebrandt went after him, but the 20th Infantry was no match for Thompson’s cavalry, and soon were out distanced.

About the 15th of July it came to the attention of the men of the 20th that a rebel named Jeff Thompson’s cavalry was raiding along the Whitewater, just 20 miles from camp. Companies E and F were assigned the task of stopping Thompson. They were to take three day’s rations with them. But here there was a problem.

The original hardtack issued to the 20th had been condemned as not fit for human consumption and flour to bake bread had been issued instead. However, there was no bread baked when the men were ready to leave; all they had to take with them was some raw ham.

Capt. Hildebrant, from Will County was in charge, and reported the problem to headquarters. He was assured that there would be bread by the time he was ready to leave. At 10 p.m., there was no bread forthcoming so Hildebrant left without it. On the way, Hildebrant purchased cornbread and some potatoes, and on this and what the men could forage, the companies were able to exist for two days.

The expedition was a failure, as it was a matter of infantry trying to catch up with cavalry. When the two companies returned to camp, Capt. Hildebrant was put under arrest by Col. Marsh for taking his men out without bread and allowing them to forage for their food. He was released two days later when almost every man of the 20th demanded his release.