Dance, drink, boat and fish … Custer Park was the place

By Sandy Vasko

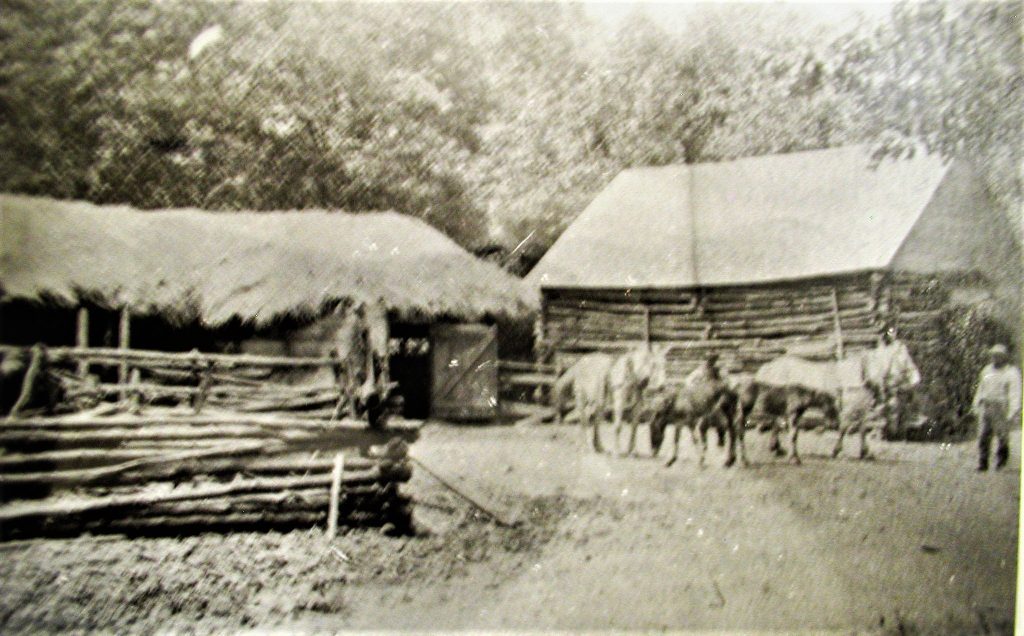

Today, we travel to the south and the Kankakee River to a small, almost forgotten village. At one time, Custer Township was a part of Reed, but the rural folks did not find anything in common with the miners in Braidwood, so petitioned to have their own township.

The petition was granted, and the township named after the recently fallen hero of the Battle of Little Big Horn. The small hamlet on the Kankakee was known as Horse Creek Dock, for the creek that enters the river at that point.

It was for a short time in its history a seaport. Well, almost anyway. You could board the little steamer named the “Mohawk Belle” at the landing and take it all the way to Chicago via the Kankakee Feeder Canal and then the I & M Canal. Or you could go the other direction to LaSalle, and this would take you to the Illinois River system where you could transfer to a paddle wheeler and on to the Mississippi. When the aqueduct over the Des Plaines River became unusable, all that stopped.

When the railroad came through town, Horse Creek Dock was no longer cut off from the rest of the world, and it saw a huge increase in business. Ice cutters in the winter, railroad folks all year around.

But the railroad was responsible for more than that. It was the railroads that decided to turn Custer into a tourist destination. Every spring, summer and fall weekend in Custer was a grand party.

As early as the 1870s, fishing parties could be found all along the banks of the Kankakee. But it wasn’t until a group of railroad men from Decatur took notice that things began to really move. We read in March of 1883:

“As the Decatur Herald predicted last summer, the Kankakee River is to prove a summer resort of no little note, and that at no distant day. Custer station, where the division of the Wabash crosses the river, has for 2 years been a private resort for Decatur anglers, and they with others will be pleased to know that the grounds in about that locality are to be improved, and the place to be made a sort of cosmopolitan resort during the summer months.”

One month later we read, “The building of a big hotel – the Astor House, at Horse Creek, was begun this week. J. J. Smillie and a Mr. Knight and others are interested in the enterprise.”

In June of 1886, we read of the year’s first big picnic, “From all accounts, the excursion and picnic by the Comet Club, of Chicago, at Custer Park on Sunday last was a big success. Eighteen coaches, drawn by two mogul engines, brought the club and its friends, whose number was estimated at 1,600. The round fare from Chicago and return was but 75 cents (about $23 today), and the receipts of the day were $2,660 ($83,000). Generally speaking, the frolic was very orderly and was much enjoyed. A few unwelcome thugs from Essex made the only disturbance reported, and they were quickly sat down upon.”

One month later it was reported, “The dancing hall in Custer Park, owned by the Wabash railway, was destroyed by fire on Sunday afternoon. The cause of the blaze is attributed to smoldering fire-crackers that fell between cracks in the flooring. The hall will probably be rebuilt at once.”

That was a busy summer. We read, “A picnic party from Chicago, numbering 800, was at Custer Park on Tuesday. It was styled a gospel meeting. “The Paper Box Makers’ Society, of Chicago, is to picnic in Custer Park on Sunday, August 8th. It is probable that a number of people from this place will attend.

“The colored Knights Templar, of Chicago, indulged in a drill picnic in Custer Park on Tuesday, and according to reports had a very orderly and enjoyable time. Many white people visited the park and spoke in praise of the orderly management.”

While the Custer folks were making money on these events, they came under a lot of criticism for allowing these tourists to party, dance and drink beer on the Sabbath. The urban people of Chicago had long since discarded the old fashion Sabbath law, but not so the rural folks in this area.

One man, a Mr. Knight who owned the land the park and dance pavilion tried to ride both sides of the fence. We read, “June 28, 1887 – Knight, the owner of Custer Park, is playing a double game. Last week the managers of the Chicago Society, called St. John the Baptist, which was to celebrate its 21st anniversary, wrote to Knight and enquired if they would be permitted to sell beer on the ground. He wrote them in the affirmative and told them that they could get their beer at $7 ($218) per barrel and their soda at 60 cents ($19) per case fresh from the ice boxes. He then rented the grounds to them for $35 ($1,100).

“After this arrangement he wrote to Sheriff Huston, representing himself as a prohibitionist, and claiming protection from the beer selling and drinking crowd which was to be at Custer Park on the Sabbath. When these facts leaked out every interested party became indignant, and expressed their opinion of the aforesaid Knight.”

There were those who, whether through jealousy or religious conviction, criticized Custer Park for her mercenary attitude toward making money on a Sunday. To appease their critics, Custer Park hosted a free Fourth of July celebration that year, to be held on a Saturday. We read in the Wilmington paper, “The patriotic people of Ritchie, Custer Park, and various stations along the Wabash have joined hands in arranging for a fine celebration and picnic on Saturday, July 3rd, at Custer Park.

“Mr. M. H. Derry will preside, and John W. Merrill, Esq., will deliver the oration. Others will also make brief addresses. Then will be a parade of ragamuffins and various athletic sports, including boat-racing on the river. Bowery dancing on a large platform will also be in order, and at evening a balloon will ascend and a fine display of fireworks will streak the air. The affair is gotten up in a patriotic spirit for pleasure and fun, and not for catenpenny (mercenary) speculations. The drive is an easy one from this city and Braidwood, and without doubt many people from both places will attend.”

There was no doubt, with the power of the Wabash Railroad added to her natural and man-made attractions, Custer Park was on the map: a working, money-making “destination.”

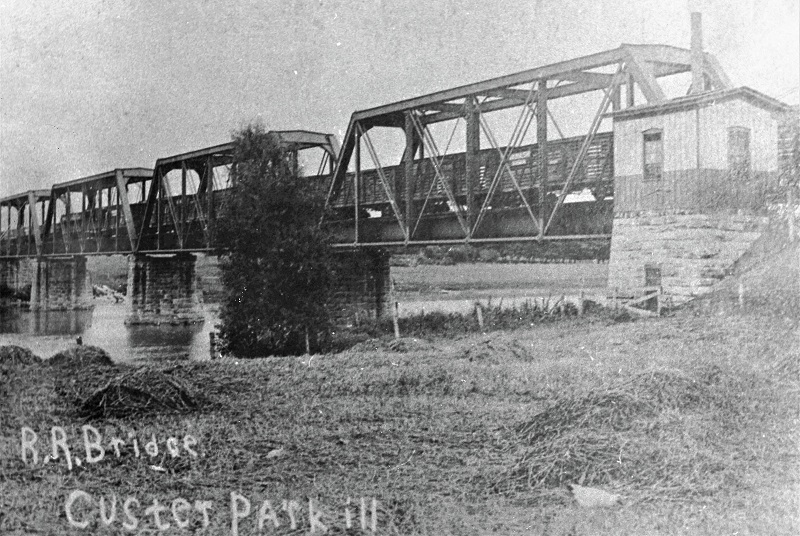

The railroad bridge at the Horse Creek Dock.